Looking Back on Cyberforce 2021

Intro

Hello! It’s definitely been a while. I was trying to keep up with weekly blog posts, but this past month, I’ve been neck-deep in preparation for this year’s Cyberforce competition, run by the Department of Energy, mainly Argonne National Labs.

Unlike the conventional “capture the flag” type competition, this event was kind of a Red v Blue, but also kind of not. It placed great emphasis on documentation, briefings, and DFIR, as opposed to killing shells or getting completely shut down. I don’t really have a structure for this post like I normally would, I’m just going to ramble my way through all of the different steps, and hope it comes out cohesive.

I. Them’s the Rules

As I’ve said earlier, I hesitate to call this competition a Red versus Blue engagement because it really wasn’t at the end of the day; it was moreso an assessment of a wide variety of security-related skills. Below is a relative timeline of events.

Omitted is getting machine access on October 25. With machine access for about a month, we had the following things on the to-do list:

- Secure and harden machines.

- Each machine had its own set of vulnerabilities planted on the system, and a variety of users to manage.

- We also had full control over how we wanted to network the machines, aside from the restriction that we could only have two extra VMs if desired.

- Deliver written documentation with the following:

- System Overview and Asset Inventory

- Network Diagram

- Known Vulnerabilities and Remediation

- System Hardening steps outside of patching vulnerabilities

- Deliver a pre-recorded “Initial Risk Assessment” presentation to a fictional C-Suite panel including:

- Summary of the Assessment

- Immediate Actions (remediation)

- Long-term Actions (remediation)

- Non-technical Descriptions of aforementioned requirements

What CEO cares that you found “RCE via insecure deserialization” on the web app?

And this is just everything that was not the day of the red team attacks. Couple this with school, other committments, and trying not to be a laptop gremlin at home, it’s honestly quite a lot. With this in mind, let’s discuss how the preparation went.

II. Cleanup Crew

Inventory

I’ll be honest, we did not spend the first week doing very much of anything. Apparently in previous years, the machines would get wiped the day of, so hardening would have to be scripted beforehand. A lot of us were busy during that first week, so most of our effort kicked in around week two, where we enumerated and hardened like our lives depended on it.

We were given access to five machines, and the credentials to the domain controller would be given on the day of. Two of the machines were managing the fictional “Kuma Lake Dam” that we were supposed to be working for, so there was some SCADA involved. In addition, there was an Ubuntu 18.04 and a CentOS7 machine that each hosted a SQL server which had the dam’s readings (e.g. temperature, rpm, etc.). And finally, we had a Windows 2012 R2 Sever which handled mail, and the primary React-powered web app that we had to maintain for Green team (volunteer users who would access our site).

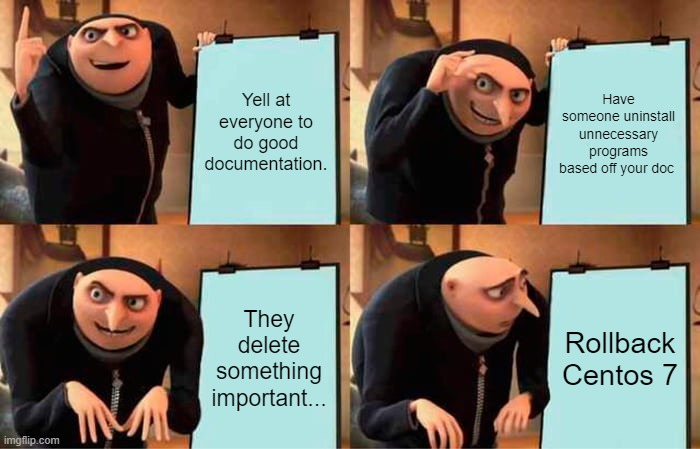

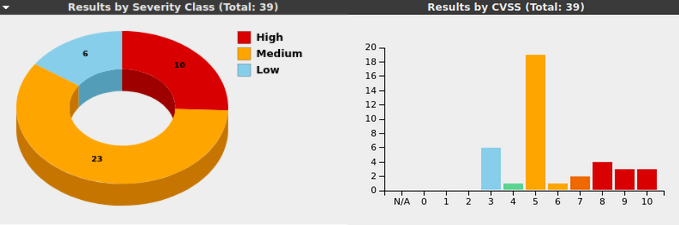

I have no clue how blue teams are actually “supposed” to do things, so my main contribution was doing a pseudo-penetration test of the machines. While other team members got their security experience from work and some from school, I was the only one who grinded TryHackMe and Hack The Box really hard. After running an OpenVAS scan on the network, I made use of some of the tools I already knew how to use, along with the tools my team showed me.

Findings

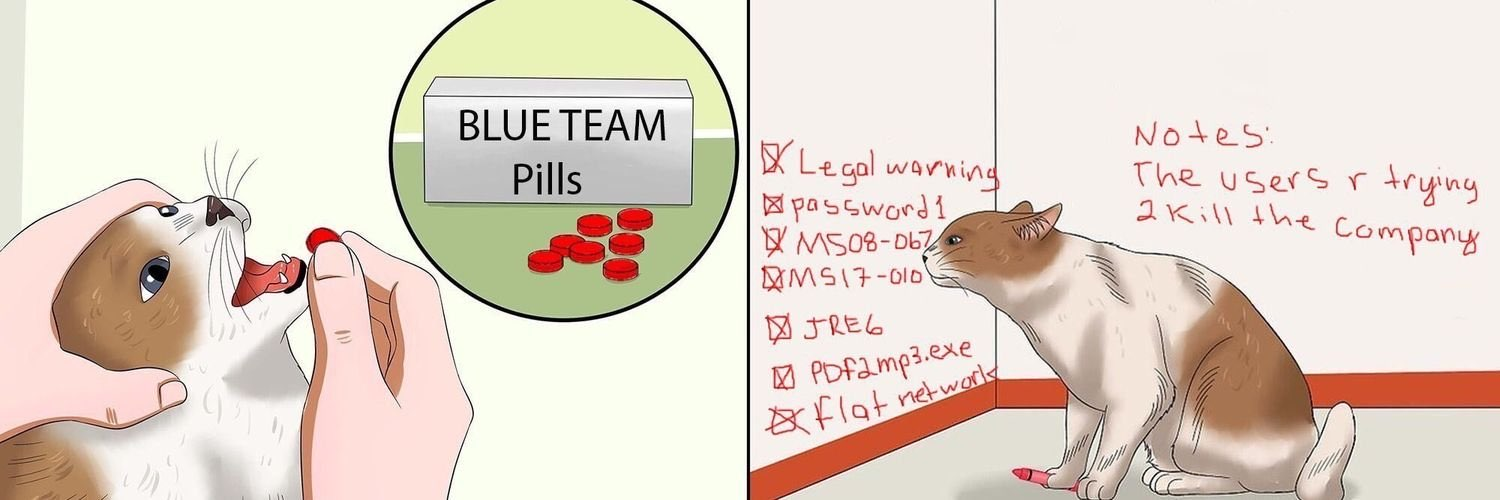

Obviously, tools aren’t everything and manual enumeration of the systems are necessary. Looking through our documenation again, there were a LOT of vulnerabilities- so much so that we were pretty sure Argonne was implying this company’s machines had been hacked before. We found a backdoor that gave a root shell on the logic controller machine. There were 3 separate buffer overflows on the Windows 2012 machine, including SLMail, which is quite literally the application they use to teach PWK students how to do a Windows 32-bit buffer overflow. Below is a brief look at what our OpenVAS scan returned.

So yeah, I guess you could say that there was a lot going on. While I went around and identified vulnerabilities and found the appropriate remediation, our team captain was setting up firewalls and Splunk, and another was fixing services that I didn’t know how to. Even while this all is happening, we’re also trying to help guide three people who had limited experience doing this kind of stuff (luckily they all came around toward the end).

Nothing I’ve written thus far can accurately depict the despair with which we were working sometimes. We popped off when something was up and running successfully, but when you find out your Windows Server has not had a vendor update since 2019, and you need to have a presentation and documentation submitted in the next four hours, it’s a little annoying. I’ve definitely learned a thing or two about system administration and searching for vulnerabilities, but the amount of effort that went in beforehand cannot be understated. Getting the documentation and presentation in was stressful.

III. Endgame

With all of the documentation in place, systems hardened to the best of our ability, the oh-so important day arrived. The day was set up like this: we would be on top of our systems from 10 AM to 5 PM CST (almost a 9-5 basically). In that time, unlike typical competitions, the red team did their work in separate phases. They had already scanned for about 3 hours the day before, and they spent the first hour or two trying to black box pen test our systems. Once they had gotten as far as they could, the main part of red team scoring began: assume breach scoring.

Assume Breach Explained

The organizers probably explained the concept on about three separate occasions, each lasting about 20 minutes, so I’m definitely over it. But, to explain it simply, rather than kill shells all day, the red team scoring was largely based on how well blue team could respond. Red team would ask us to give them a shell, we had to comply, and they might plant some malware or create some kind of persistence method. It was then up to us to find their stuff, and basically talk through it interview-style.

For example, red team says, “Hey, we’ve put a file on your system that’s connecting to the outside. Tell us the name of the program, and the IP and port connected to it.”

Then we have to go in and find what they’re asking of us. Suppose we find the file in Downloads. We run netstat -an to find the program, and we give our response. They ask follow-ups, we supply answers. We then get points for our ability to respond.

Obviously, there’s positives and negatives to this. I’ll talk more about this later, but it was neat to have things to respond to, but also kind of boring.

Monitoring

We had split up our team into having various responsibilities. Our team captain was telling the new people exactly what machine they should be monitoring on, and how to keep track of what things might be going on. Meanwhile, another teammate and I grinded out “anomalies” (basically just CTF challenges).

While I wasn’t actively monitoring, I am happy that we were able to teach some of the basic monitoring techniques that are available on Windows and Linux (that I know of at least). I showed some of the tips and tricks I had picked up during TryHackMe King of the Hill matches and watching HackTheBox Battlegrounds (still haven’t played that one yet). Since I can’t speak to how monitoring with Splunk and other tools went, I’ll at least drop some links in case people want to learn.

- Ippsec - HTB Battlegrounds

- THM King of the Hill Guide

- Noxtal’s Ultimate KotH Guide

ss -tulpn,netstat -tulpn,ps -aef --forest, etc

Anomalies, aka The Hardest CTF

Cyberforce likes to be unique and call their CTF challenges “anomalies”. Some of them are straight up challenges, others are “trivia” (but not really) over security, networking, and NIST concepts. Now normally, CTFs are 24-72 hour events, or sometimes less based on context. Our competition was only about 7 hours. Now, upon first glance, you say, “That’s totally a normal expectation”, and to that I say.

What.

There were about 50 anomalies to work through. There were around 15 quick, “trivia” ones. I would say another 10-15 were pretty quick (e.g. dumping hashes from registry hives, cracking password hashes). That leaves around 20-25 anomalies to be done in under 8 hours, which means we had to HUSTLE.

Over the summer, I competed in Argonne’s “Conquer the Hill” CTF and placed in the top 10, so I felt pretty good coming into this. Little did I know that they would truly step up their game for this event. There was some malware reversing, a memory dump, code review, and more (writeups on some of my favorite ones soon). While some of the challenges were still poorly designed (in the sense that I could just strings file | grep flag), I think these were huge improvements over the ones I’ve seen before, and I hope the anomaly team continues to improve (and maybe let me help out? :D).

IV. The Aftermath

I am writing this blog on November 14, 2021. It has been a full day since the end of the competition, and I don’t really have any strong feelings on the event. Feels weird to not have to stay up until 12:00 AM anymore (unless I’m really procrastinating). Winners are officially announced in a couple of days.

Overall, I think the event went quite well. The incorporation of hardware systems like a modbus service and Node-RED was unlike most other competitions. Hosting the infrastructure in Azure with VPN access as opposed to NetLabs was way better since it made copying and pasting way easier, and I could also use my own machines. The emphasis on documentation was also very good.

As for negatives, I think a lot of my points are very nitpicky. I personally would have liked to see more genuine red team activity as opposed to “Hey go find this thing”. “Assume Breach” is cool and all, but I think that model of red team scoring really undermines the whole hardening and securing thing we had been slaving over for hours. The team captain who was working on firewalls had to scrap his work for the past 2 days because they didn’t say that all of the ports needed to stay open until just before the day of the event. Furthermore, while our team did not have huge problems with this, other teams were upset that their red teamer was not very responsive, likely due to a disparity between red team volunteers and blue teams. Other than that, I think I’ve already said all that I feel needs to be said. (I also kind of wish Active Directory was actually relevant to the competition but it ended up not being important which was depressing for me but that’s neither here nor there.)

If you are a college student in the United States looking for security experience outside of CTFs, I highly recommend you try and put a team together to compete in this competition. While it isn’t a true red v blue competition, I think there’s valuable experience to be gained, especially with the things off of a terminal. This is especially directed towards my hardcore HTB or THM people who have never had to do things outside of a terminal in their life.

The hands-on terminal work is only about half the battle.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading. Hopefully I’ll be able to get at least one writeup on some of the anomalies out before Hack The Box University CTF this weekend, see you then!

And now for homework… ;-;

PS. No guarantee I’ll be able to keep up the weekly pace. I’ll probably only do a writeup on a box if it was especially interesting to be totally honest.

Comments