Intro

I graduated (I don’t know if I’ve said that here yet), and in the 3.5 years I was in university, I competed in cyber-related competitions every year. Not only CCDC, the big American one, but also the Department of Energy’s Cyberforce Competition (and their own side events) and various CTFs. On top of that, I also did a “non-technical”, policy-focused circuit from the Atlantic Council called Cyber 9/12, and I’ve placed relatively well in all of these events at one point or another.

I definitely haven’t been at the top, or quite frankly, that close to the top, and I don’t claim to be the absolute best at this (I’m not). However, I’ve had mild successes, decent placements, and many more failures. All of this is to say, there are a lot of things I think about when I look back on some of these events, and while I reflect on what I’ve done so far, I figure it’s a good idea to go over some of the biggest mistakes/lessons I made during these events.

Lesson 0: y u heff to be mad, it’s just a game

![]()

I’ll keep this one short, and I hit on this at the end, but competitions are games, and are merely approximations/simulations of what may happen in the real world. No matter how much organizers from the government or other independent competitions want to say that this will prepare you for the real world, there are many aspects of real world security practice that aren’t covered or simulated very well by the competition.

As such, you can “cheese” a lot of the stuff in a competition. If red team has historically tried to lock people out of machines (e.g. changing passwords and then rebooting the machine), then make backdoors for you to get back in. Make it a hostile environment for attackers. This may not be sustainable in the long run, but you’re only dealing with attacks for 8 hours.

Are you defeating the purpose of the event? Sort of. Is this what a lot of people/teams do? Absolutely. Stay within the written rules, but know that there are shortcuts that you can take in events that maybe aren’t so appropriate anywhere else.

Lesson 1: Knowing Your Attack Surface

Good asset inventory should be more than just “OS + IP Address”. Try to keep track of services/ports that should be up, what users should be on a box and whether they’re an admin or not, subnets, etc.

forgetting to change web admin credentials during red v blue event and just getting absolutely blasted for 5 hours straight pic.twitter.com/izG83CCNh7

— an00b (@An00bRektn) February 19, 2023

This might have been the lowest moment for me in any competition.

This tweet comes to us after a Midwest CCDC qualifier, where I felt we had an extremely strong team (that is, no one was completely new and needed to catch up), but we got extremely owned for making a simple mistake, that is, not changing default web credentials.

If you’re in a red v blue competition, assuming it goes for even a few hours, it is extremely important to stay organized and to keep tabs on what it is you’re actually defending. A network topology is nice, but do you actually know what’s running on your network, or who’s accessing it? This sound extremely basic, and I know some people reading might think I’m stupid for making this mistake (you’re not wrong for thinking that), but it’s 100% worth keeping tabs on things like:

- Web applications and other network services

- Domain names and the overall state of DNS

- Credentials you use to access boxes and applications

- Users you expect to login to machines, applications, databases, etc.

- What a machine “typically” looks like (e.g. if you see a PowerShell process that isn’t yours, that’s something you should look at)

- And more, depending on the type of environment.

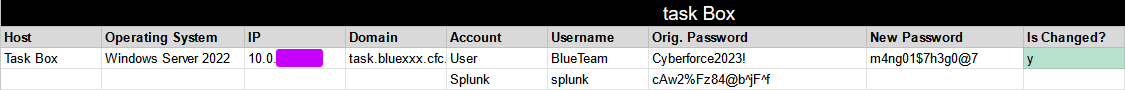

During Cyberforce, my team liked having a Google Sheet with all of the credentials we use for our accounts, or any other important passwords that we should know, an example shown below.

We had other documents to help us keep track of inventory, but I’ll let you, the reader, figure out a way to make a system the way you want it. When you have a good understanding of what your assets are actually doing, you can be way more efficient and effective with how you choose to lockdown the network. For instance, if you have a Linux box running MySQL, but nothing is actually using it, there’s no need to keep that up.

Lesson 2: Having a Game Plan, Setting up for Success

From minute zero, everyone should have a unified game plan for what they’re going to do for the first hour. This should be coordinated, and each team member should have their own specialty going into it.

In addition to having good inventory, it’s important to actually figure out what it is your team plans on doing. The age old advice for any leader is going to be knowing how to delegate, but no one ever explains how delegation is a two way interaction. The vast majority of teams that compete in these events are not all crackhead security gods that have won events, work in the industry, and have mentors that know all of the tricks of the trade. In my case, while we had a mentor/coach that knew what he was talking about, that doesn’t immediately help when only ~3 people know what they’re doing, and the rest of the team is in the middle of an Intro to Unix class.

You do not want your team to devolve into two people downloading Roblox on the Windows workstation because everyone knows there’s no shot of qualifying for the next stage.

This is all to say, know what your team is and isn’t capable of. If I have a new person on my team who wants experience, but has never done sysadmin stuff before, I’m going to outline very simple tasks like copying over our own SSH configurations or initially changing passwords. Then, I’ll keep them seated next to someone who’s working in the same area (e.g. Linux machines, AppSec, etc.) so they can have someone they can ask. On the other hand, if I have someone who has experience, for instance, with networking, I’ll play to their strengths and have them work with the firewall.

Rob Fuller aka mubix has a very good slideshow from 2016 titled “How to Win CCDC” that I think still holds up to this day and covers a lot of similar ideas that I am here. What I will add to what he says in this slideshow is that part of “Risk Prioritization” is, after figuring out separation of roles in the team, is having a game plan during the event. There is no reason anyone should be sitting idly during the first hour, minute, or even second of the event. Good game plans don’t need to have every hour mapped to the tee, but are instead just detailed enough for your team and are flexible enough to account for disruption. Here’s a rough sketch of what I did during one year at a qualifier for MWCCDC, as a team captain/incident responder/threat hunter:

- Early Game (Hour 0 - 2)

- Make sure tools get downloaded and set up on all of the machines

- Make sure everyone has run their initial configuration setup scripts for hardening

- Take care of any issues that come up with NetLABS access or the above

- Mid Game (Hour 2 - 6)

- Priority: Make sure scored services stay up

- Delegate injects to relevant parties (e.g. give policy-related), respond to injects I can complete quickly

- Search through Domain Controller for any misconfigurations we missed, reduce AD attack surface

- Continue to help people with any questions that come up, check in with Firewall Admin

- Nothing to do? Start hunting for threats and filling out incident response reports if needed.

- End Game (Hour 6 - 8)

- Finish/Delegate as many injects as humanly possible

- Address the most pressing mishaps during the event (they will happen)

I never wrote any of this down, this was just something I had in the back of my mind during the event so I always had something to do. You’ll notice I spread myself a little thin, which is true. I’m not saying this is what you should do, but knowing the layout and spread of the team, I was the only one who knew TTPs well enough to do IR/Threat Hunting.

As a final note, I’ll also add that part of the game plan should be figuring out what you want to add to the network. It’s pretty common for there to be no logging and monitoring in place, or even firewalls, so you should try to figure out what it is you need (again, dependent on the team). Splunk may be good on paper, but if no one on the team knows how to use Splunk, and it’s only a week before the event, maybe use a SIEM next year and figure out what will actually be useful and serviceable to your team. It’s also possible that the environment you’re given has limited resources, so deploying a Security Onion or ELK stack might crash a system and prove to be a bigger headache than you want.

Tools that might be useful:

- SysmonForLinux

- Kunai

- Suricata

- Custom eBPF-based tooling? (example: mttaggart/bluebpf)

Lesson 3: Automate the Boring Stuff

If you know you’re going to take x, y, and z hardening steps on a machine, don’t bother doing it manually, automate it!

During my very first Red v Blue event, the only thing I did was change settings in /etc/ssh/sshd_config on one Linux machine, and then spammed the who command in my terminal to watch for attackers. now i type ps aux | grep pts instead

Obviously, there’s room for improvement here.

Different competitions operate, well, differently. Some give you the infrastructure days in advance to solely scout out, and then all of the configuration has to happen on the day of. Others let you make the changes ahead of time. This lesson mainly applies to the latter, but in all cases, automation is valuable, and is something you should invest time into. Instead of manually configuring SSH on competition day, if I know what settings I’m going to change without being in the environment, and I’m allowed to bring my own scripts, why wouldn’t I?

For another example, on Windows, I know that no matter what the machine is, I’m (a) going to install Sysmon and (b) setting a login warning banner. Of course, there are more things you could do, but let’s keep it to two for the sake of simplicity. I can then write a PowerShell script to run lines like this:

# ...trimExpand-Archive -Force $tools\SysinternalsSuite.zip $tools\SysinternalsSuiteInvoke-WebRequest "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/user/repo/main/config/sysmonconfig-export.xml" -Outfile $tools"\sysmonconfig-export.xml"Move-Item $tools\SysinternalsSuite\Sysmon64.exe C:\Windows\System32\Sysmon64.exeC:\Windows\System32\Sysmon64.exe -i $tools"\sysmonconfig-export.xml" -accepteula

# Set BannerSet-ItemProperty -Path "HKLM:\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\System" -Name "legalnoticecaption" -Value "*** * * * * * * * * * W A R N I N G * * * * * * * * * ***"Set-ItemProperty -Path "HKLM:\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\System" -Name "legalnoticetext" -Value "######################################## \n This computer is the property of Example Corp \n UNAUTHORIZED ACCESS WILL MAKE US UPSET (WE CANT CALL THE AUTHORITIES BECAUSE THIS IS A COMPETITION) \n########################################"# trim...As long as this script is tested, you have now saved at least 5 minutes of valuable time making sure things get put in their spot correctly, and can now focus on more pressing matters (like checking user descriptions in AD, or ordering food, things of equal importance).

If you want to take your game up a notch, maybe figure out an even faster way of deployment. After watching ippsec explain Ansible Playbooks, I’ve not only adopted it for events when applicable, but for configuring my own local VMs, an (outdated) example of which you can find here. Maybe Ansible is all you need, but maybe there’s even more projects out there that can help you with this.

Lesson 4: On Incident Response

Incident Response, as far as events go, is about reporting and remediating. Bad IR only gets one or none of those things done.

So you’ve been hacked, what now? In the real world, collecting evidence, triaging what happened, and getting a report out quickly is the biggest part of it. Especially in that case, you may end up having to provide information to law enforcement or some other party. However, in competition land, there is no law enforcement to bring in, and it’s on you to both report it and make sure it doesn’t happen again in the span of a few hours.

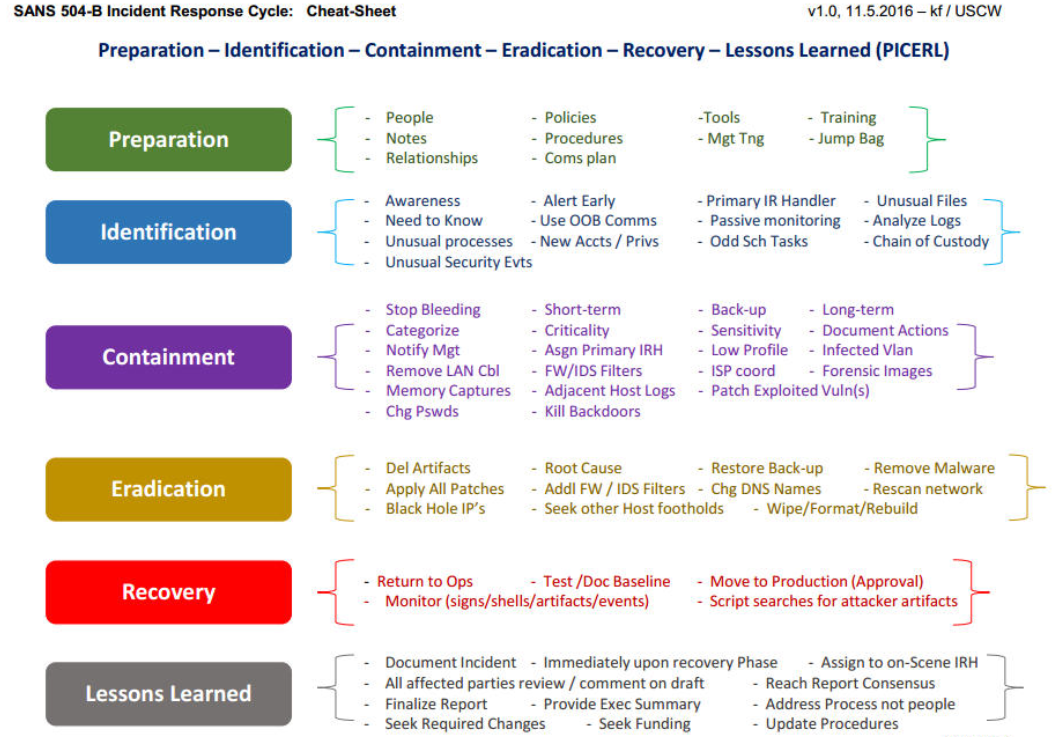

Although there’s a difference between what happens in the game and what happens in real life, PICERL is a good framework to work off of in both cases:

Source: SANS

Source: SANS

In the context of a one-day Red v Blue event, you’re running through all of these steps extremely quickly. An in-depth discussion of what to do when you see something bad is well beyond the scope of this blog, but your goal in a report should be to provide as much information and evidence as possible to outline how you think the breach went, and the steps you took to fix it.

There have been so many times where I’ve had an incident happen (normal), but then no actions are taken to remediate it because everyone’s confused.

To avoid that nightmare scenario, it’s important to make sure that the people that are skilled enough to investigate incidents (or hunt for them) aren’t getting completely pulled away from that when they need to investigate things. Multitasking/context switching is expected in high-pressure environments, but having your lead incident responder also be the person who is the Active Directory expert of the group is a *problem*. If your event requires you to submit incident response reports, have a template ready to go that is not only valuable to the people that are grading you, but also valuable for your own team to reference.

Aside from the preparation, it’s important that you’re not immediately killing shells. Take a minute to try and figure out how the attackers got in, and once you have a rough idea with some evidence, start closing things off and patching. Red teams at these events can also be extremely quick with persistence, so have a checklist of places they’ll drop stuff. Whether it’s your run of the mill cybercriminal or volunteer red teamer, they’re lazy, and they won’t change things up unless they absolutely have to.

Lesson 5: On Red Team TTPs

No one is dropping 0days at CCDC, you just forgot to change the root password.

This one doesn’t stem from a mistake I made, rather, my #1 pet peeve during the Red Team talkback after most events:

Red Teamer: Any questions from the students?Person 023: Yeah, we saw red team take down our systems multiple times, so we were wondering if red team had any 0days with them?If a volunteer group of hackers for an event had 0days, they would be more likely to report them for bug bounty or even sell them to fishy buyers for profit before spending them on a competition that has zero bearing on the real world.

I have yet to be on the red team for collegiate competitions, but as someone who knows the basics of offensive security (at least, I’d like to imagine so), they are probably just finding the weakest links in your network that you missed. From what I’ve seen in the past, some commercial tooling like Cobalt Strike is on the table, but the red team at these events has much better things to do than to burn their novel AMSI bypass that might end up getting uploaded to VirusTotal.

So what’s the fix here? Really, it’s just about knowing how attacks actually go, which these days, is not very hard with how many courses and platforms there are to start learning.

Addendum: Competitions =/=> Getting a Job

This part is a little bit informational, a little bit of a rant, but I felt like it was important to touch on. This post, at the time of writing, is around the same time as online user assume breach’s posts (Part 1, Part 2) about what they perceived as being the reality of pentesting/consulting. In response, discourse occurred, but as a recent graduate, a lot of the stuff on the topic of the job market resonated with my own experiences.

“The job market is HOT for cyber people, but cyber people that have 10 years experience as a web app pentester, client facing consulting experience, CVEs and have given talks at conferences. They won’t have a problem finding a home. The market is not hot for people that turn off Real Time Protection to run their MSF payload.”

It’s extremely common to see the statistic on how many jobs in cyber there are right now being touted as a way to get people interested in the industry, but if you look up jobs for “Security Engineer”, “Security Analyst”, “Penetration Tester”, “Security Consultant”, etc., you’ll very quickly see the overwhelming number of senior-level roles being listed.

The point of bringing this up is not to add fire to the flame, but for me to just be honest and say that even if you:

- Write a blog that has a couple of well-recognized posts and has won money

- Compete in a variety of events related to information security, business, and public policy

- Make projects and host them publicly

- Engage with the infosec community online to help others out, or just lurk to learn things

- Have a degree in Computer Science

there is no guarantee you’ll immediately find a spot in the security industry. And maybe that changes in the future, who’s to say really. But for me, at least, the reality is this: (1) I only have two degrees and a Security+ to my name and (2) competitions are not substitutes for real experience (according to “the industry”).

They’re games. Games that are rooted in some real-world activity, but games nonetheless. In a competition, you don’t have to worry about longevity, you just have to worry about what gets you there to the end of the game. In a competition, you don’t have to get your changes approved by someone higher up, you just do them. In a competition, you’re told there’s a red team going. They’re great ways to get familiar with real world tools in a short amount of time, but I don’t imagine they ever garner the level of respect you might want from them outside of the related community, unless it’s something as big as DEF CON finals or making top 8 at CCDC.

Competing in infosec-related events has definitely been a highlight for me over the last four years, and I probably won’t ever stop entering CTFs or playing Hack The Box. But, as I’m at a point where I need to actually do something after undergrad, the realization of where these events stand for someone who wasn’t the GOAT but also wasn’t horrible, really sets in. Don’t get me wrong, competitions are a great way to level up your skills and be challenged with problems that change the way you approach situations. Without them, I wouldn’t have the skills I do now, and I love them for that. I’m also proud of certain placements or events for my own growth and what I was able to accomplish, even if I never closed or didn’t get to the biggest stage. That said, in my experience, there’s certainly diminishing returns that get downplayed in the name of marketing. I’m down to be wrong here, but if the barrier to entry is spending hundreds or thousands of dollars on certifications, or being the top 0.01% of people doing infosec, marketing training platforms, courses, and competitions as ways to break in is, well, sad.

I like hacking for hacking’s sake, and I wouldn’t be doing it if it wasn’t for the love of the game, but it’s clear that trying to make it a career is more of a beast than I thought it would be. I don’t mean to end on a doomer note (this ended up being more of a rant than I originally intended), but I figure I should drop this in for anyone who thought they’d get something more tangible out of it than I did. I’ll still be here doing my thing though, and I’m hoping to get more things done in this time I have without school or a job.

gg we go next