Intro

Everyone does these, you know the drill already.

In November of 2024, my job paid for an Offsec Learn One subscription for me to complete the Advanced Web Attacks and Exploitation (AWAE) course, and the OffSec Web Expert (OSWE) certification. After grinding the course out in a little over two weeks, I took the exam on March 19th, and as of March 22nd, I am officially OSWE certified.

Like I said with my CPTS Review, I could make this about “how to prepare for the exam” and such, but the topic has already been posted about so much that I don’t know if it’s worth adding to the pile.

Anyway, here’s my thoughts about the whole package.

But first, let’s give some context

The course ($1749 btw!!) is structured as a series of case studies in real open-source applications (with the exception of one app, but that module is really good), where you go from some form of authentication bypass or account takeover, into exploiting some kind of server-side vulnerability to get RCE. Instead of being like the OffSec version of PortSwigger Academy, where they teach you new vulnerability classes, the ethos of AWAE seems more geared towards tracing the flow of data within applications and understanding a system well enough to find critical vulnerabilities.

Each module comes with an interactive lab that you can follow along with with the exact application installed. Outside of the labs, there are six additional challenge labs, which resemble what you’ll be dealing with on the exam. Additionally, each module comes with its own set of “Extra Mile” challenges, that dive deeper into the various applications, usually asking you to probe further, automate something, or run an exploit differently.

The exam is a proctored, 48 hour long assessment (plus an additional 24 for reporting) where you are presented with two web applications to hack. There are flags for different objectives, and you have to achieve a minimum score of 85/100 to have any shot at passing. Like the labs and the course, you’re provided with a debugging machine to work through your exploit before running it on the real thing. On top of that, you need to write a report detailing your exploitation process and prepare a script for each box that will execute your full attack chain (i.e. run the script, get reverse shell).

As I said earlier, I grinded this course out in two weeks. Would I recommend that to other people as a feasible timeframe? Absolutely not.

I currently work as a pentester, I’ve been playing CTFs since 2021, I have an intermediate level of reverse engineering experience, and I’ve done Hack the Box’s CPTS as well as PortSwigger’s BSCP. I came into this course not planning on learning new vulnerability classes, I came here to get better at code review. To be totally transparent, I skipped many “Extra Miles” and even an entire module just to make sure I got to finish the material before I had to go back to the 9-5. If you are uncomfortable with web exploitation, I would highly recommend taking your time. Most people take anywhere from 8 weeks to 6 months.

The Good

Overall, I would say I really liked the course, which I’m honestly surprised to say given OffSec’s reputation in the past. Do I think it’s $1.7k good? Probably not. But I wouldn’t call it straight up bad or outdated.

One thing I’ve come to realize is that in the journey to get good at something, the first steps always feel like leaps, one after the other. First you learn about how HTTP works, then you understand the structure of the web application, and then every new vulnerability class you learn feels like something fresh and exciting. But then you get to a point where you’ve learned the basics, and you kind of just, plateau? You know what a SQL injection is, how it gets introduced, how prepared statements defend against it, but you’re not doing a great job consistently being able to identify when it does or doesn’t exist in the wild.

OSWE, for me at least, was the kind of course I needed. We learn by doing, and OSWE’s approach felt like the right one for me to clean up the gaps in my approach. By going through several different case studies and taking more time to dig into what certain syntax is actually doing, it really helps to develop your intuition and troubleshooting skills when it comes to evaluating how vulnerable something actually is. Every module takes a slightly different approach to identifying bugs. Feeling out these various methodologies and understanding how you can incorporate each into your own workflow really solidifies the process of navigating through pretty large code bases.

I’ve historically not been a huge fan of web security, but I was so engaged during some chapters like the Prototype Pollution module, not because the vulnerability class was particularly interesting, but because of what they did with it. The whole module walks through identifying a server-side prototype pollution vulnerability, and then spinning that alone to RCE via polluting attributes in templating engines, which involved extensive reverse engineering of various templating engines’ compilation/lexing flows. I mean, they were doing tricks on it, it was wild.

Not all modules are built equally, as we’ll get into later, but I do think there’s something valuable to digging into why certain payloads work. Why does insecure deserialization give RCE? How does this common SSTI payload work in the first place? How can we do more with SQL injections?

The Bad

While I did enjoy the course as a whole, and the only thing I had to pay with was my time, there’s a couple of things I should point out.

1749 USD. 175 Chipotle Burritos. I just couldn’t pay that amount out of pocket for this, I’m sorry. Even though I haven’t taken it, I would still buy the OSCP for this amount because then it would get HR to shut up about arbitrary certifications. This website documents a bunch of resources to learn about the different vulnerabilities, and this repo has links to install some of the applications that you attack in the source. If you’re strapped for cash, I would frankly just look at the syllabus and find the vulnerabilities yourself.

“So I did some offline grinding”. Despite my praise being that the course is about methodology, some modules really like to skip ahead to the exploitation, omitting the actually hard part of working through 100+ potentially vulnerable calls. For instance, in the first real chapter, on ManageEngine, the module essentially does this:

- We see that their pattern for making SQL queries is like this. Let’s build regex to find all of the SQL queries.

- Here’s a bunch of results! This first one we found could be vulnerable, but it requires authentication, let’s keep looking!

- Eventually, we find the vulnerable route.

What do you mean “eventually”? How did you narrow down 100 different routes? Was it all manual, did you have better regex???

Not all modules are like this, but some of them just seem to glaze over details that would’ve been valuable to see. In hindsight, I guess there were videos I didn’t watch, but I highly doubt they stray from the written material that much.

A lot of this stuff breaks in the cloud. The existence and impact of file upload vulnerabilities is way less likely in a time where apps are written for the cloud. The impact and feasibility of SSRF is lessened on a well-hardened EC2. Between this and how limited the number of vulnerabilities in course is (there’s at least 3 different examples of SQL injection), I wouldn’t expect to find some of these attack chains in the wild, though there is still value in going through them.

The Lab Environments. After realizing I had to set my VPN’s MTU to 1200, the labs were actually quite responsive. The two Windows modules run on Windows 2012 images, which is kind of a slog to get through, but it gets much more responsive once the rest of the targets are Linux. However, some of the challenge labs, especially the ones that have significant WebSockets or emulated users, feel somewhat unreliable and hard to get working consistently. I didn’t run into any stability issues on the actual exam, but it’s unfortunate that some of the only practice you get for the exam can be so inconsistent you feel like skipping over it.

Long sessions or bust. I don’t know if this is just a me thing, which is why I left this for last, but by virtue of being structured as case studies, it feels very difficult to learn anything without being able to commit a 2-4 hour block just to work through a module or challenge lab.

Varying Levels of Pedantic. Another minor qualm, again having to do with how the quality in modules varies. Sometimes, they’re written pretty well and walk through steps in a very logical order. Other times, it feels almost overly academic, sometimes manufacturing reasons for things that can really just be chalked up to “I just stumbled upon it”.

The Exam

The exam, quite frankly, was probably the most chill part of the entire experience. Having 48 hours dedicated to just testing without being interrupted by meetings or life was just nice, especially when you go into it with the knowledge that you can get RCE on these applications. Obviously, I can’t speak to what’s on the exam, but I will say that I successfully obtained the flags needed for 85 points in only 12 hours (could’ve been less if I wasn’t so stubborn). Here are my tips to set you up for success on the exam:

Before the Exam

Approach the pre-exam prep however you like, but this is what worked for me:

Take your time with the course. Even before getting into the exam itself, I think the best approach with the course is to try and find the vulnerability hinted at by the module title yourself. If the module is “SQL Injection to RCE”, go try and find that vector first. If you’re stuck for an hour or two, look back at the course until you feel like you need the full walkthrough. With only a few hints, I was actually able to figure out the ErpNext module mostly on my own, which was a great confidence boost and let me work on my own methodology.

Prepare your automation ahead of time. Some of the exploits in this course can take time. Scanning networks/ports with SSRF, blind SQL injection, writing helper scripts to predict tokens, etc. Having template code prepared ahead of time that you can just drop into your final exploit script (which you should also probably have a template for) will save you tons of time on the exam. In fact, I wouldn’t even wait until the challenge labs to practice automation, try automating the exploits in some of the labs! It’ll give you good practice and awareness for what you need to know.

Do the challenge labs (and most of the Extra Miles). The challenge labs are the single closest practice for the exam, so be sure to seriously dig into at least half of them. As of writing, there are now 6(?) different applications, which is maybe less than people would like. However, I would say the challenge labs are the best representations of the kinds of apps you’ll see on the exams, so I would for sure set aside time to do them. I got to look at maybe 3/6, but only really solved 2, though I’ll probably go back and check them out.

Additionally, most Extra miles will deepen your understanding of the applications, so I would also recommend doing them as you go through the course. Some people say you should do all of them, I don’t think you really have to, but giving each of them an attempt for 30-60 mins and then asking the Discord or forums for a nudge is a perfectly acceptable strategy. I definitely skipped a few, and even if I had more time, I probably wouldn’t do all of them (I don’t feel like exploiting the same vulnerability with 4 different templates, 2 is probably enough).

Do some additional reading. Some people have recommended trying various HTB boxes, challenges written by other students, or even other courses. I didn’t really end up using these resources at all, but what I did find useful was just reading about more web attacks and learning different styles of approaching an attack surface. They won’t map one-to-one with the exact vulnerabilities in OSWE, but I think the thought process is valuable to hear. Here are some highlights that I’ve seen recently:

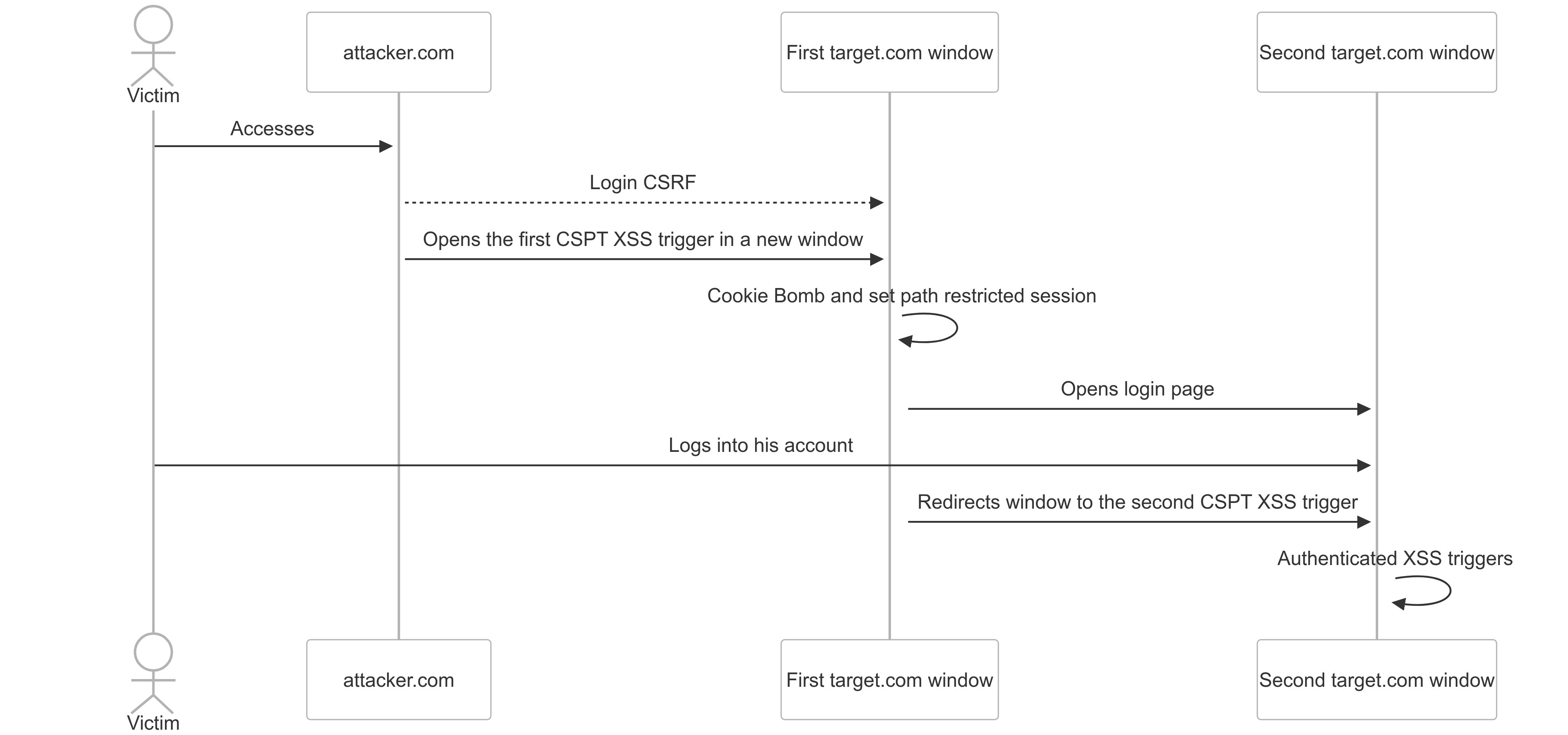

- busfactor - Hacking High-Profile Bug Bounty Targets: Deep Dive into a Client-Side Chain

- hacefresko - A very fancy way to obtain RCE on a Solr server

- Creastery - Send()-ing Myself Belated Christmas Gifts — GitHub.com’s Environment Variables & GHES Shell

- srcincite - just the whole blog tbh

That CSPT chain is so crazy I’m still not over it (source: busfactor

That CSPT chain is so crazy I’m still not over it (source: busfactor

During the Exam

Take breaks and take them often. Staring at VS Code for 6 hours straight will do you no good. Even though the exam is proctored, you can take breaks whenever you want, so I would use them liberally. At one point, I drove a full 30 mins away to get food and boba from one of my favorite spots, came back, ate food, took a short walk, and came back to the exam having a much clearer head than I did before. You have enough time to take breaks, don’t let the panic consume you.

Identify your routes. Understanding the routing of your application tells you where your entry points are, and can help inform your code review process. If you’re looking for unauthenticated vectors, don’t start by looking at the admin routes.

Ask yourself why. I covered this in the CPTS review, but it’s especially true for this exam. If you find a potentially vulnerable piece of code, but can’t seem to exploit it, don’t run to PayloadsAllTheThings and start throwing stuff at it. Take a minute, breathe, and ask yourself “Why can this work?” In doing so, you’ll probably take a closer look at where user-controllable data is flowing and what variables you actually have control over, giving you a much more level-headed mentality.

Make sure your exploit scripts work. This one sounds obvious, but I decided to do a final test of my scripts 30 minutes before my lab time was over, reverting the target machines and running the exploits on a fresh deployment. One of them worked fine, but the other immediately threw an error. Luckily, I already had an idea as to why that could happen, but I frantically spent the 30 minutes taking additional screenshots and modifying my code to work properly. The exploit scripts should be considered a deliverable and not an afterthought.

Leverage the debugging VM. In my experience, you usually don’t get the opportunity to have a setup where you can debug an application in a white box assessment. However, if you have a clone of the target VM where debugging is mostly setup for you, I would definitely make use of it. Even if you don’t want to debug the source code, using database logging to view queries as they come in live, or simply having the ability to instantly give yourself an admin account to work from can be insanely valuable and make your work more efficient.

Take good notes. A key part of the course and exam is developing a good enough understanding of the application that you can take typically low-risk issues and spin them to be more severe. If something doesn’t seem vulnerable at first, don’t completely ignore it, just take note of what you’ve tested and what you’ve concluded from it. The code bases are large enough where notes are worth the time, but not too large that you can’t go through them enough in 48 hours. Also take a lot of screenshots, they’ll come in useful if you forget something while reporting.

FAQ

On a completely arbitrary scale, how would you rate the difficulty from 1 - 10? Quality from 1 - 10?

Difficulty: a light 7/10

Quality: also a light 7/10

I’ve already voiced my opinion on the good and bad here. I don’t think the web vulnerabilities themselves are particularly difficult, but the apps are built in such a way that you have to consider the big picture, which is something that only gets easier the more you practice.

Favorite Modules: Prototype Pollution (Chips), DotNetNuke, OpenITCockpit Least Favorite Modules: Rudderstack, APIGateway/Directus (SSRF)

How much coding knowledge is required?

I don’t have a background in web development apart from one software engineering class I took in university, but through doing CTFs, I think my ability to quickly mock up scripts in Python has gotten pretty quick. As far as the exploit scripts go, if you think you could write your own tooling in a language of your choice, like a web fuzzer or a port scanner, you have enough knowledge to be comfortable on the exam. All you really need is familiarity with your language’s HTTP requests library and knowledge of control flow structures (i.e. loops and conditionals). One thing to note: some modules have you exploit weak token generation or hashing, and it’s usually easier to just copy and paste that section of that web app into your own helper script, so it is important to feel good enough about modifying source code in other languages.

As for actually doing code review, if you have sound computer science fundamentals where you can see variables, loops, conditionals, etc. and follow a variable as it passes through the code, you’re probably good. That kind of skill really comes with time, but if you want practice, a lot of web challenges on the Hack the Box platform are completely white box and are often written in a variety of languages.

Is this only doable by experienced web testers?

Not necessarily. I don’t know if I’d even call myself a web expert at this point yet. Having strong fundamental web knowledge will take you a long way here. The exam doesn’t have any funky HTTP Request Smuggling, Cache Deception, or injections in obscure languages, but it will force you to think about whether or not filtering just < and > is effective, or the differences between MySQL and PostgreSQL.

Is this course/exam relevant in 2025? Has this helped you in real pentests?

I’ve touched on this throughout the post, but overall, I’d say the overarching themes are still relevant in 2025. The methodology and approach to following flows within source code, evaluating the effectiveness of defenses, and the foundational HTTP/browser knowledge are all truly evergreen. In fact, the Concord module, covering an attack path where weak CORS and a lack of CSRF protections can lead to more sophisticated cross-site requests, was extremely similar to an attack path I found on an engagement recently. Of course, not every case study shown in the course is as realistic or even that common, but I think the true value of the course is in working through the case studies and internalizing the process as opposed to learning new vulnerabilities. If your intent in pursuing OSWE is the latter, the course really doesn’t always do the best job, and you’re better off hitting up PortSwigger Academy.

Do I need to do X before doing OSWE?

I can firmly say that everything you need to know for the exam is in the course. However, and I think I’ve been repeating this throughout the blog, go develop good web fundamentals before diving into this. You shouldn’t be learning about XXE for the first time if you’re trying to finish this course in < 1 year.

How does this compare to BSCP, CBBH, and CWEE?

BSCP is an offering from PortSwigger that focuses on quickly identifying vulnerabilities without source code. The cert was pretty easy compared to OSWE, not because the vulnerabilities were easier, but because BSCP does not stray very far from the labs at all, so if you get close to 100% on PortSwigger Academy, it almost becomes a pattern recognition game.

CBBH is Hack the Box’s foundational web certification, and as time goes on and they slowly rework and add to the course, some of my information may be outdated. That said, CBBH is strictly black box (unless there’s some source code leak on the exam, I haven’t taken it, so I wouldn’t know), and focuses on your classic web vulnerabilities. CPTS covers most of CBBH, so I can say that the course made me much better at exploiting server-side vulnerabilities, because many of the challenges force you to work through the methodology yourself, but it’s still relatively simpler compared to CWEE and OSWE.

CWEE the Hack the Box version of OSWE, and I can’t really speak to it at all since the modules are all tier 3, i.e. out of range of the subscription I currently have. I trust the folks at HTB Academy to make good content, but I can’t help but look at the outline and wonder how good it really is. I see mention of OAuth and SAML, which is a very realistic thing to include, but then also mention of TLS downgrades and DNS rebinding, which is cool but not what I necessarily expected. Also looking at the exam format, apparently they expect you to give patches for the vulnerabilities you identify, which is tough. Here’s a message from someone who’s passed both exams:

And here’s a Medium post from d415k, who was the first person to pass the CWEE: link

Conclusion

Very thankful to the people that supported me to finally get this done. OffSec certs had been out of reach for a while due to the cost, so being able to have one under my belt feels very good, and I look forward to tackling some others when I have the free time.