Intro

I have spent the last 6 days nonstop playing HackTheBox’s Cyber Apocalypse CTF with 7h3B14ckKn1gh75, and it’s probably been my best in-event performance to date. The event was great, our team managed to get ~35 challenges solved (13 of which were done by me :D ), and there’s a lot of great content to be brough over here.

Prior to the event, I was grinding cryptography content over on CryptoHack (lovely people over there, please go check them out), and a lot of it came into play here. We’re starting with “The Three-Eyed Oracle” a 1-star difficulty challenge that involved a single encryption oracle, but one that encrypted your input sandwiched between some random bytes and the flag. The fatal error made is the usage of ECB (electronic code book) mode to encrypt, which I can exploit by slowly trickling in bytes of the flag to a block that I can bruteforce characters on one at a time.

Description

Feeling very frustrated for getting excited about the AI and not thinking about the possibility of it malfunctioning, you blame the encryption of your brain. Feeling defeated and ashamed to have put Miyuki, who saved you, in danger, you slowly walk back to the lab. More determined than ever to find out what’s wrong with your brain, you start poking at one of its chips. This chip is linked to a decision-making algorithm based on human intuition. It seems to be encrypted… but some errors pop up when certain user data is entered. Is there a way to extract more information and fix the chip?

Exploring the Challenge

If you’re unfamiliar with cryptography challenges, they can operate in two main ways.

- You’re given the algorithm used to encrypt some plaintext along with set output values (no interactive instance), and must find some way to get back to the original plaintext.

- You’re given access to a remote instance that will dynamically interact with your input, to simulate some kind of modified chosen plaintext or chosen ciphertext attack.

This one was the latter, so we’re given some downloadable content, and a docker container to interact with to perform our actual exploit/algorithm on.

Source Code Review

Unlike web challenges, I like heading to source code immediately.

from Crypto.Cipher import AESfrom Crypto.Util.Padding import padimport randomimport signalimport subprocessimport socketserver

FLAG = b'HTB{--REDACTED--}'prefix = random.randbytes(12)key = random.randbytes(16)

def encrypt(key, msg): msg = bytes.fromhex(msg) crypto = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_ECB) padded = pad(prefix + msg + FLAG, 16) return crypto.encrypt(padded).hex()

def challenge(req): req.sendall(b'Welcome to Klaus\'s crypto lab.\n' + b'It seems like there is a prefix appended to the real firmware\n' + b'Can you somehow extract the firmware and fix the chip?\n') while True: req.sendall(b'> ') try: msg = req.recv(4096).decode()

ct = encrypt(key, msg) except: req.sendall(b'An error occurred! Please try again!')

req.sendall(ct.encode() + b'\n')

class incoming(socketserver.BaseRequestHandler): def handle(self): signal.alarm(1500) req = self.request challenge(req)

class ReusableTCPServer(socketserver.ForkingMixIn, socketserver.TCPServer): pass

def main(): socketserver.TCPServer.allow_reuse_address = True server = ReusableTCPServer(("0.0.0.0", 1337), incoming) server.serve_forever()

if __name__ == "__main__": main()Aside from all of the socket programming stuff, the program is pretty simple. There’s only one function, encrypt(), which will take our message and do the following:

- Use the PyCryptodome library to initialize an AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) object in ECB mode (more on that later), with a random 16-byte key

- Concatenate a prefix of a random 12 bytes, our message (converted from hex), and the flag

- Return the encrypted value

For people unfamiliar with cryptography as a whole, this might seem like a near impossible task. AES is the NIST standard for symmetric encryption and has only been shown to have breaks in very specific scenarios, and bruteforcing a 16 byte key will mean there are 2^128 different keys that could exist. Luckily, we don’t need to worry about AES at all, because of the poor choice of encryption mode.

Background: Block Ciphers and Modes of Operation

Block Ciphers

There are many ways to construct a cryptographic algorithm, but the two major categories are symmetric encryption, where you use the same key to encrypt and decrypt, and asymmetric encryption, where you use one key to encrypt, and another to decrypt.

Block ciphers are a subset of the symmetric encryption category that all have one thing in common: they operate on blocks. A plaintext message is broken up into blocks of a static amount (e.g. 16 bytes, 32 bytes), and then each one of those blocks has the algorithm applied to it. This, of course, is a very generalized definition that can encompass a variety of constructions, but it’s important that we set the stage for what’s to come.

Modes of Operation

When you’re dealing with one block, things are pretty easy. Run algorithm, get output. But what do you do when you have multiple blocks? This is where modes of operation come in, governing exactly what to do when you have multiple blocks.

But can’t we just run the same algorithm on each block and have it be scrambled?

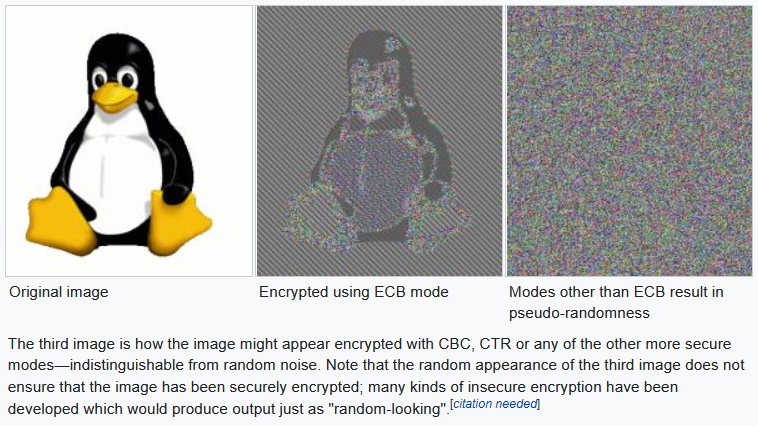

![]()

What you have just described there is called ECB mode, or Electronic Codebook mode. It’s the naive approach, and while it is hard for a human to pick it out in text, it’s clear why it fails when you try and encrypt something more visual.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

The goal of encryption, informally speaking, should be to make that penguin look like random bytes, kind of like the far right picture. But, using ECB mode, we still see the penguin, because the same plaintext block will always encrypt to the same ciphertext block. So, the rule of thumb, NEVER EVER EVER USE ECB MODE.

I’ll briefly cover two other modes here just so you know what good encryption looks like.

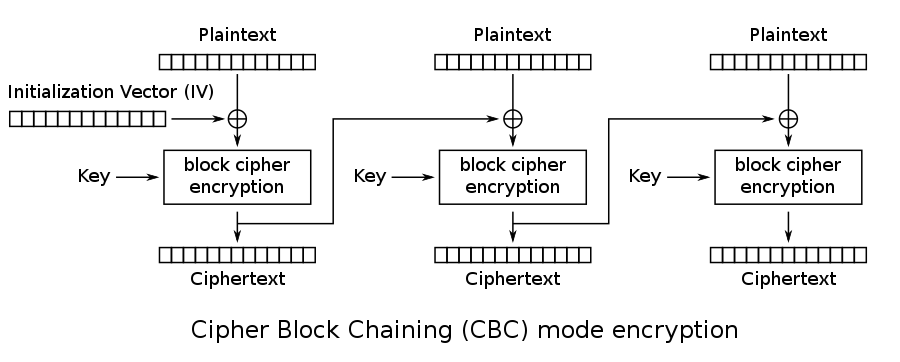

CBC (Cipher block chaining) mode will take the previous ciphertext block and XOR it with the next plaintext block to cause each block to have an effect on the next, so it’s not as easy to reverse. You’ll notice the inclusion of an “Initialization Vector” (IV) in the diagrams. This is because it would not be in our best interest to let the first block be the same between ciphertexts encrypted with the same key (think about the magic bytes at the top of every file or something similar). The solution, then, is to include a random block known as the IV to be XORed with the plaintext and sent with the message so it’s not feasible to glean the same information.

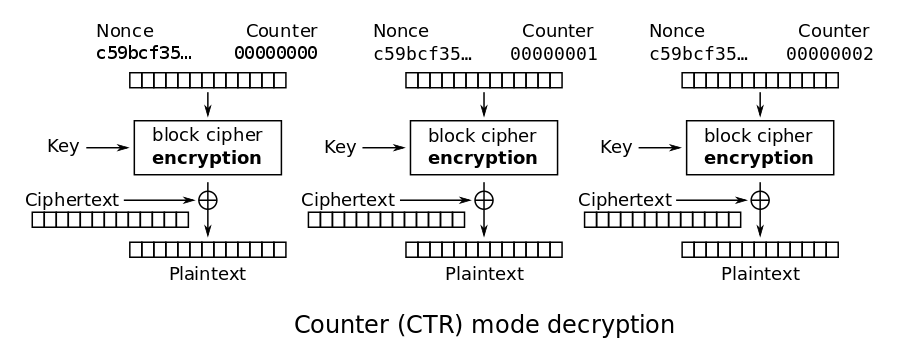

CTR (Counter) mode turns a block cipher into a stream cipher by encrypting a counter value, then XORing that with the plaintext. It might not seem secure, but it actually is, becuase if the underlying encryption function is secure, XORing it with the plaintext, in a way, is like doing a one-time pad. However, since the keystream is not pure random, it isn’t at the level of security that the one time pad is. You’ll notice there isn’t really an IV here, but a “nonce” instead. A nonce is a “number used once”, which is a non-random value that is typically used to bootstrap an IV and should never be reused. Here, we’re not using an IV, but the nonce, simply put, is obfuscating what the counter is at.

Grabbing the Flag

Strategy

Ok. So ECB is bad. Now what?

I first learned the method to this by reading this article by Zach Grace, and I recommend reading it. However, I’ll summarize it here (thank Zach for the graphics).

Suppose I could pad out my input to perfectly fill a certain amount of blocks, and I wanted to leak the stuff ahead (because that’s where the flag is). First, I’ll need to find the offset to be able to fill up a whole block with whatever I want:

Once I do this, I know exactly what the block “AAAAAAAA” encrypts to. Recall the secret we want to leak is ahead of our input. So, by removing one “A” from my input, we see the following:

At this point, I know that my encrypted block is the encryption of “AAAAAAA_” plus some unknown character, because I don’t know what the flag is. However, since this is ECB mode, I can just bruteforce a block for all ~90 characters that would show up in a flag by submitting them to the oracle, and comparing each against what I have here. Once I’ve determined that the last letter is H, I can pull back the curtain further to include the T. Since I then know what “AAAAAAAH” encrypts to, I can basically repeat the process until I leak the entire value.

So, no AES necessary. Just some good logical thinking to break our encryption!

Final Script

As per usual, I’ll write the script and then explain what I did.

#!/usr/bin/env python3# Reference: zachgrace.com/posts/attacking-ecb# Note that this is, in the conventional definition of it, NOT a padding oracle attack# but it has the spirit of one.from pwn import *

r = remote('134.209.177.202', 30382)

def oracle(plaintext: str): r.sendlineafter(">", plaintext.encode('latin-1').hex()) return r.recvlineS().strip()

flag = ""p = log.progress(f'working...')while True: padding = 'B' * 4 +'A' * (31-len(flag)) ref = oracle(padding) for c in range(33, 126): ct = oracle(padding+flag+chr(c)) p.status(f"\n ct: {ct[64:96]}\n ref: {ref[64:96]}\nflag: {flag}\n pad: {padding+flag+chr(c)}") if ct[64:96] == ref[64:96]: flag += chr(c) break if '}' in flag: break

success(flag)I’m using the pwntools library to simplify some of the network communication that needs to be taking place, and it also features a very nice logging setup so I can see the inputs more visually without blowing up my terminal. So, let’s walk through the code.

- The

oracle()function is simply an easy way for me to send my desired message, and recieve the result without having to repeat those lines. It was more useful during testing, but also makes the code more legible. - We begin the loop by creating a

paddingvariable. Remember that there were 12 bytes of junk preppended to our message, so to get to 16 bytes (as indicated by the padding and key size), we add 4. We then create two blocks of A’s, not only to check our offset, but also to simplify some of the coding process (no weird substring stuff with the flag)- That padding message is then used as a reference for us to bruteforce against.

- We iterate over the characters that would normally show up in a flag, and submit a version of the payload where we guess the payload.

- If the

refblock matches thect(ciphertext) block, we know we’ve found the right character, and can add it to the flag and repeat.

- If the

When we run the exploit/script/whatever, it takes a minute, but we eventually get the flag.

kali@transistor:~/ctf/cyber_apocalypse/crypto/crypto_the_three-eyed_oracle$ python3 solve.py[+] Opening connection to 206.189.126.144 on port 32676: Done[↑] working...: ct: 0e7b569943d74c74c8f8d3985693b89a ref: 0e7b569943d74c74c8f8d3985693b89a flag: HTB{345y_53cr37_r3c0v3ry pad: BBBBAAAAAAAHTB{345y_53cr37_r3c0v3ry}[+] HTB{345y_53cr37_r3c0v3ry}[*] Closed connection to 206.189.126.144 port 32676Flag: HTB{345y_53cr37_r3c0v3ry}