Intro

Just got done playing in corCTF 2022 organized by the Crusaders of Rust CTF team, and this was probably the hardest event I’ve ever done. So hard, in fact, that by only completing 8 challenges (including the survey and welcome challenge), we somehow got 119th/978 which I’ll take for a small team. I only did a grand total of 3 challenges, so I almost wasn’t going to post about this at all, but I thought some of these were worth going through as a lesson in modular arithmetic and why we should learn computer science and math without worrying about the direct security implications.

tadpole

Crypto - 262 solves

Description

tadpoles only know the alphabet up to b... how will they ever know what p is?

Challenge

from Crypto.Util.number import bytes_to_long, isPrimefrom secrets import randbelow

p = bytes_to_long(open("flag.txt", "rb").read())assert isPrime(p)

a = randbelow(p)b = randbelow(p)

def f(s): return (a * s + b) % p

print("a = ", a)print("b = ", b)print("f(31337) = ", f(31337))print("f(f(31337)) = ", f(f(31337)))We’re given the output of the file, which is \(a\), \(b\), \(f(31337)\), and \(f(f(31337))\).

Solution

This is a fairly simple modular arithmetic problem, so I’ll take this as an opportunity to talk about the very basics here, not only because this is a short solution, but because almost half of the crypto challenges used what is known as a linear congruential generator (LCG). An LCG, for our intents and purposes, is a function of the form:

It makes use of what’s known as the modulo operation, which, simply put, returns the remainder from division (e.g. ). A modular congruence can also be rewritten as an equation. Continuing the example:

The | means ‘divides’, as in, 3 divides 5-2 without having a remainder. The \(n\) is any arbitrary integer that satisfies the equations.

Coming back to the generator, we’re basically taking a linear function and doing a modulo operation, to get this (rather primitive) psuedo-random number generator, where all outputs are in the range . For instance, if I have the LCG , and set ‘s’, the initial seed, to 4, the outputs look like this:

You’ll notice that the outputs are looping, which is something that naturally occurs in any LCG. We call this the period, and while we tend to avoid using these in real RNGs, a longer period makes the LCG stronger. The details as to calculating the period and evaluating the strength of a LCG are beyond this writeup, but now we have the basic information to tackle this challenge.

In our case, we are given the LCG with the multiplier and the increment, but the flag has been encoded into the decimal value, is confirmed to be prime, and is the modulo for our function. We’re also given two outputs from the function, and . If we take some time to write out what everything means, the answer becomes apparent very quickly. From what we know about rewriting moduli, we can get two equations:

Unfortunately, we don’t know what or are, and trying to brute force them would take far too long considering the sizes of the numbers. However, we do know every other value here. Observe that and actually have a common factor, that is, . Since we know the rest of the numbers in this equation, we can rearrange the equations to find these two quantities, and then take the greatest common divisor to find the prime, which is our flag.

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytesfrom math import gcd

a = # long numberb = # long numberf_1 = # long numberf_2 = # long numbers = 31337

pn_1 = f_1 - ((a * s) + b)pn_2 = f_2 - ((a * f_1) + b)p = gcd(pn_1, pn_2)

def f(s): return (a * s + b) % p

assert f_1 == f(31337)assert f_2 == f(f(31337))

print(long_to_bytes(p))flag: corctf{1n_m4th3m4t1c5,_th3_3ucl1d14n_4lg0r1thm_1s_4n_3ff1c13nt_m3th0d_f0r_c0mput1ng_th3_GCD_0f_tw0_1nt3g3rs}

luckyguess

Crypto - 150 solves

Description

i hope you're feeling lucky today

Challenge

#!/usr/local/bin/pythonfrom random import getrandbits

p = 2**521 - 1a = getrandbits(521)b = getrandbits(521)print("a =", a)print("b =", b)

try: x = int(input("enter your starting point: ")) y = int(input("alright, what's your guess? "))except: print("?") exit(-1)

r = getrandbits(20)for _ in range(r): x = (x * a + b) % p

if x == y: print("wow, you are truly psychic! here, have a flag:", open("flag.txt").read())else: print("sorry, you are not a true psychic... better luck next time")Solution

We’re definitely not going to spend as long talking about modular arithmetic this time. Here, we’re presented with a remote server and another LCG, this time with a known prime (specifically a Mersenne prime but that only speeds up computation), and randomly generated, but known parameters. The goal of this “game” is to give the LCG an initial seed, and then predict the output after the LCG has been run ~\(2^19\) to \(2^20\) times.

Although the random library is being used, which does not use a cryptographically secure RNG, we never get enough values to predict the next output, so that is out of the question. We only have control of the seed and predicting the amount of times the LCG will run is out of the question, so our only option is to find some value for x such that it returns the same number, which looks like this:

It’s pretty simple. We just do the following arithmetic.

One important thing to note is that with modular arithmetic, we do not just divide like you normally would. Without going into the details of the properties of a mod p field, think about it like this: in the same way that dividing by a number is like multiplying by the reciprocal in “regular” math (e.g. ), with modulo, instead of “dividing”, we multiply the inverse, defined by multiplying any number by the inverse , such that . For instance, in a modulo 5 field, the inverse of 2 is 3, because \(2*3 = 1\pmod5\). In Python, we can do this using the pow() function, raising a number to the -1 power and doing a modulo p.

from pwn import *

context.log_level = 'debug'r = remote("be.ax", 31800)

r.recvuntil(b"a = ")a = int(r.recvlineS())

r.recvuntil(b"b = ")b = int(r.recvlineS())p = 2**521 - 1

info(f"a = {a}")info(f"b = {b}")x = (b * pow((1-a), -1, p)) % pr.sendlineafter(b'enter your starting point:', str(x))r.sendlineafter(b'alright, what\'s your guess?', str(x))

flag = r.recvlineS()success(flag)flag: corctf{r34l_psych1c5_d0nt_n33d_f1x3d_p01nt5_t0_tr1ck_th15_lcg!}

whack-a-frog

Forensics - 154 solves

Description

Come play a game of Whack-a-Frog [here](https://whack-a-frog.be.ax/) and let all your anger out on the silly msfrogs. Due to lawsuits by Murdoch, we were forced to add DRM protection, which has allowed us to detect a player distributing copyrighted media. Thankfully, we took a pcap: can you make out what he was sharing? Make sure that anything you find is all typed in UPPERCASE and is wrapped like corctf{text}. Best of luck and enjoy whacking some frogs!

this one isn’t crypto but i did it so leave me alone

Challenge

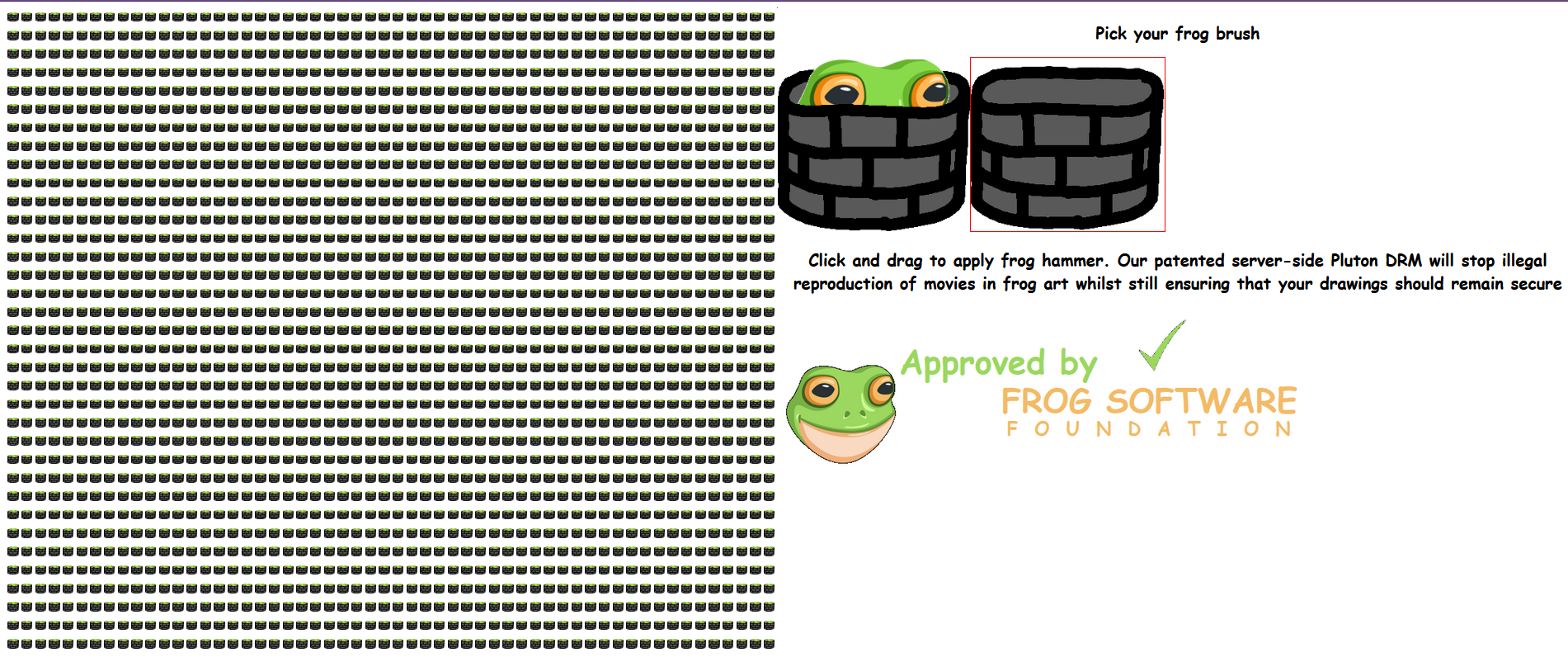

We’re brought to a fun website where you can hide or show various frogs to draw things.

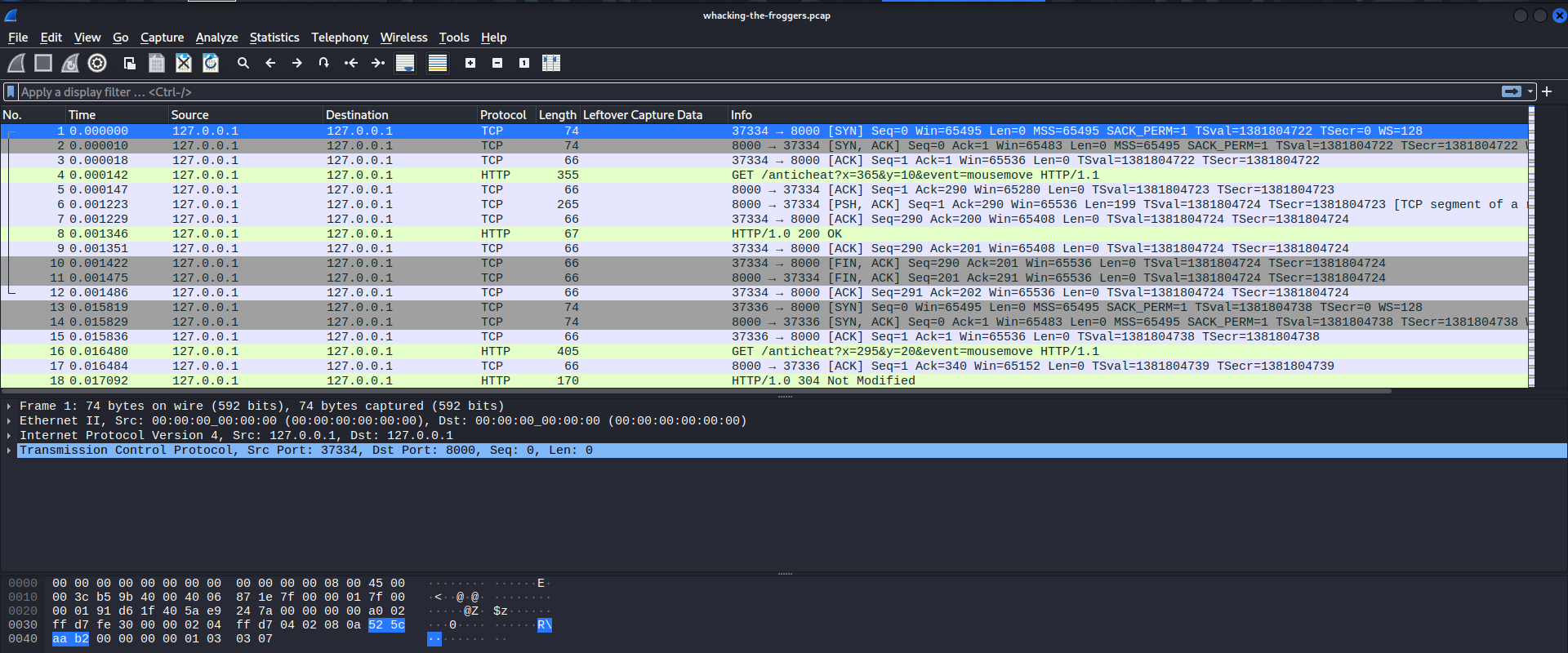

Very hard to see to be honest. Regardless, we’re also given a pcap file which contains traffic from someone’s usage of the website, which we can view using Wireshark.

Very hard to see to be honest. Regardless, we’re also given a pcap file which contains traffic from someone’s usage of the website, which we can view using Wireshark.

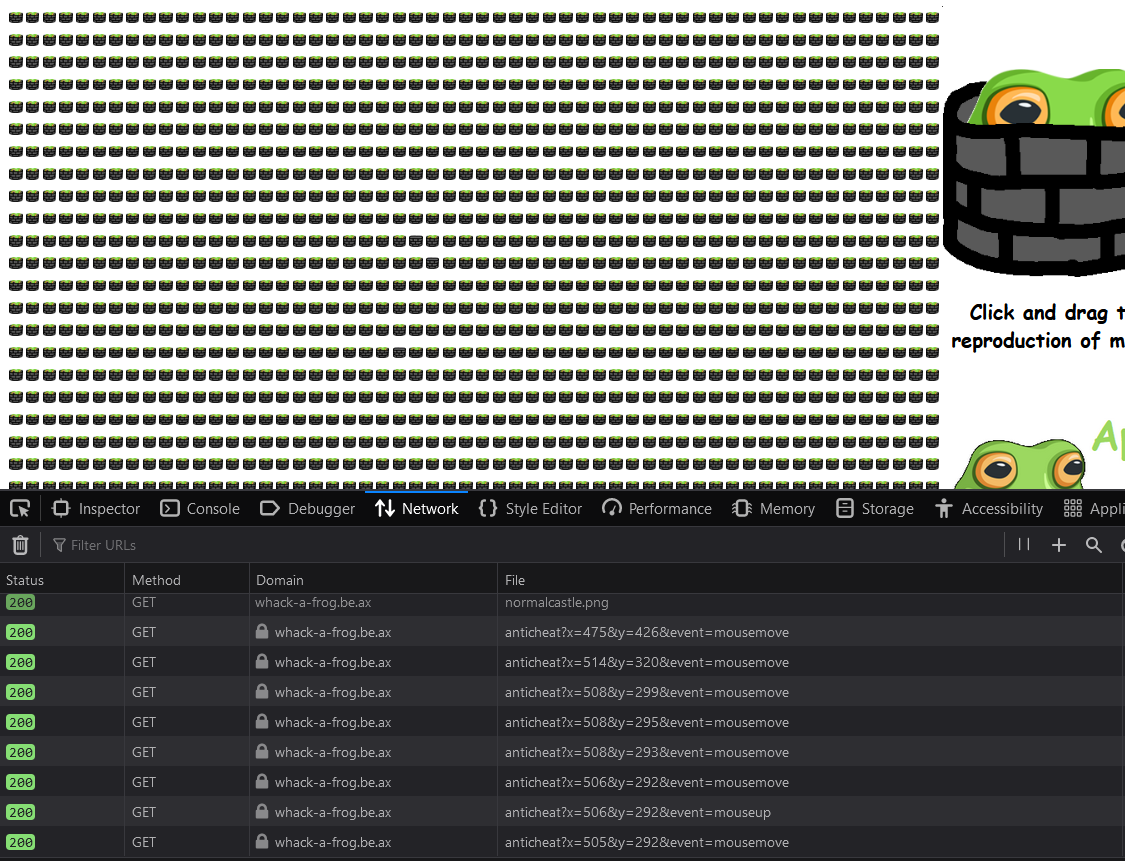

We see a bunch of HTTP reuqests being made to a /anticheat endpoint, containing an x-y coordinate pair and a mouse event: mousemove, mousedown, or mouseup. Looking back at the webpage, we can see these requests being made live using the developer tools.

It doesn’t really seem like there’s that much else going on, because the coordinates seem to be relatively accurate to what my mouse is doing.

It doesn’t really seem like there’s that much else going on, because the coordinates seem to be relatively accurate to what my mouse is doing.

Solution

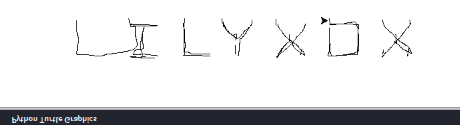

There’s two main parts to this: (1) parsing out all of the motions as shown in the packet capture and (2) recreating the motions. Credit for taking care of the first part goes to bakki, using the pyshark library to only pull out the URLs that had mouse information. I then took that data, parsed it out, and then used turtle, (yes, that turtle you were forced to use in Python 101) to recreate the drawing.

Why use :msfrog: when 🐢?

import turtleimport timeimport pyshark

# Credit bakki for doing the hard part of actually parsing the pcapdef extract_URIs(): pcap_path = "./whacking-the-froggers.pcap" uri_list = [] packets = pyshark.FileCapture(pcap_path, display_filter="http.request and http.request.uri.query")

print("[*] Parsing packets...") for pkt in packets: if pkt.http.request_full_uri: uri_list.append(pkt.http.request_full_uri) packets.close() print("[+] Parsing complete.") return uri_list

def parse_instruction(line): line = line.split('&') x = int(line[0][2:]) y = int(line[1][2:]) event = line[2][6:] return (x,y,event)

if __name__ == "__main__": uri_list = extract_URIs()

# lets parse it so we only get the coordinates of the cursor: instructions = [query.replace("http://0.0.0.0:8000/anticheat?", "").strip() for query in uri_list]

# Why :msfrog: when 🐢 window = turtle.Screen() window.setup(2000,300) t = turtle.Turtle()

t.penup() for line in instructions: x, y, event = parse_instruction(line) if event == "mousemove": t.goto(x,y) elif event == "mousedown": t.goto(x,y) t.pendown() elif event == "mouseup": t.goto(x,y) t.penup()

time.sleep(20)The pyshark library lets us apply a filter that only pulls HTTP requests and the query, which we then do some additional filtering and string slicing to get into a format we like. From there, we just read the values and have 3 different if conditions, one for each mouse state, to recreate the image.

That might not look like words, but if you flip it vertically…

flag: corctf{LILYXOX}

Bonus Round: CryptoCTF

I never made a post about this but I did also play in CryptoCTF a few weeks ago with the CryptoHackers from CryptoHack, not because I’m good at cryptography, but because I wanted to learn from the best. I didn’t actually solve a single challenge, but I went back and did the two easy ones on my own after they had been solved because I wanted the experience. The only one I’m doing a writeup for is for Klamkin, because Baphomet was a fairly easy encoding one. The reason I’m putting this here is just another reminder as to why I need to study modular arithmetic some more.

Description

We need to have a correct solution!

Challenge

We don’t get any source code, but we do get a netcat command, nc 04.cr.yp.toc.tf 13777 (that still works as of writing, surprisingly). Upon access, we see this:

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| Hello, now we are finding the integer solution of two divisibility || relation. In each stage send the requested solution. Have fun :) |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| We know (ax + by) % q = 0 for any (a, b) such that (ar + bs) % q = 0| and (q, r, s) are given!| Options:| [G]et the parameters| [S]end solution| [Q]uitEntering ‘G’ will give us the values for q, r, and s. Entering ‘S’ prompts us like so

| please send requested solution like x, y such that y is 12-bit:Spoiler alert, even after you get this right once, you have to do it for increasing bit sizes for x and/or y.

So, what do? If we were not forced into having a specific size for x or y, we could always submit (r,s) or (0,0) since the two congruences are “structurally”, for lack of better words, the same. But, in the above example, our first prompt tells us ‘y’ has to be between and . Since it’s implied by the challenge that there are multiple solutions, and that the math isn’t very heavy, we will always set the constrained variable to to ensure a valid length. From here, we do some more modular arithmetic like we’ve been doing to solve for y.

Just to break down these steps, we start with the congruence containing ‘r’ and ‘s’, and then solve for ‘a’. From here, we substitute into the congruence containing ‘x’ and ‘y’. Both terms contain a ‘b’, which cancels out. Then, we multiply both sides by ‘r’ and the inverse of ‘s’. Since ‘x’ is the only unknown, we can solve this to have a valid ordered pair. We can also take that same result and solve for ‘x’, if and when needed.

Solution

from pwn import *import re

context.log_level = 'debug'

R = remote("04.cr.yp.toc.tf", 13777)

R.recvuntil(b"uit")R.sendline(b"G")

q,r,s = [int(i) for i in re.findall(b"\d+", R.recvuntil("Options"))]

# Credit to uvicorn from the CryptoHack discord for figuring this one outdef solve_y(bits): y = (2 ** bits) - 1 x = (y * pow(s, -1, q) * r) % q return (x,y)

def solve_x(bits): x = (2 ** bits) - 1 y = (x * pow(r, -1, q) * s) % q return (x,y)

R.sendline(b"S")

for i in range(5): R.recvuntil(b"such that ") prompt = R.recvlineS() if prompt[0] == "x": ans = solve_x(int(re.search(r"[\d]+", prompt).group(0))) msg = f"{ans[0]}, {ans[1]}" R.sendline(msg.encode('latin-1')) else: ans = solve_y(int(re.search(r"[\d]+", prompt).group(0))) msg = f"{ans[0]}, {ans[1]}" R.sendline(msg.encode('latin-1'))

R.recvuntil(b"flag: ")flag = R.recvlineS()success(flag)flag: CCTF{f1nDin9_In7Eg3R_50Lut1Ons_iZ_in73rEStIn9!}

Conclusion

CryptoCTF and corCTF have been the hardest events I’ve done, for the sole reason that the stuff that I glazed over while learning the basics get exploited real hard. It’s a super valuable lesson to learn, and I’m definitely going to be more diligent in my reading from here on. Huge props to the Crusaders of Rust team for putting on a great event and an even more insane set of challenges (kernel pwn? new web research? an accidental 0day?).

And if you want to do CTFs with me, feel free to join our Discord. I created Inactive Directory on a total whim but it’s been fun hanging out with people and helping others learn.

Also follow me on twitter @An00bRektn, don’t know if I want to rebrand to something else or not but bigger number better person.